A bladder cancer diagnosis often raises many questions. To help provide you with clear and patient-friendly answers, we recently spoke with Dr. Elizabeth Plimack, a leading medical oncologist at Fox Chase Cancer Center. Dr. Plimack’s primary focus is caring for people with genitourinary cancers with an interdisciplinary approach.

In this conversation, Dr. Plimack explains the different types of bladder cancer, how it’s typically diagnosed, and how treatment decisions are made. View the full webinar for deeper insights into bladder cancer.

The following questions and responses have been lightly edited for grammatical purposes.

1) What are the main types of bladder cancer, and how do they differ?

Dr. Plimack: Bladder cancer is actually very common. Most bladder cancers stay on the surface of the bladder, almost like a wart that grows there but doesn’t invade or cause major issues. We call that non–muscle invasive bladder cancer. It can be treated in different ways. If it’s low-grade, we often manage it with scrapings and close monitoring. If it’s high-grade, we may need to put treatment directly into the bladder to clear it.

Our urologists are incredible, and the field has advanced a lot. We now have many options for intravesical therapy, which means treatments placed into the bladder to target disease that’s limited to the surface.

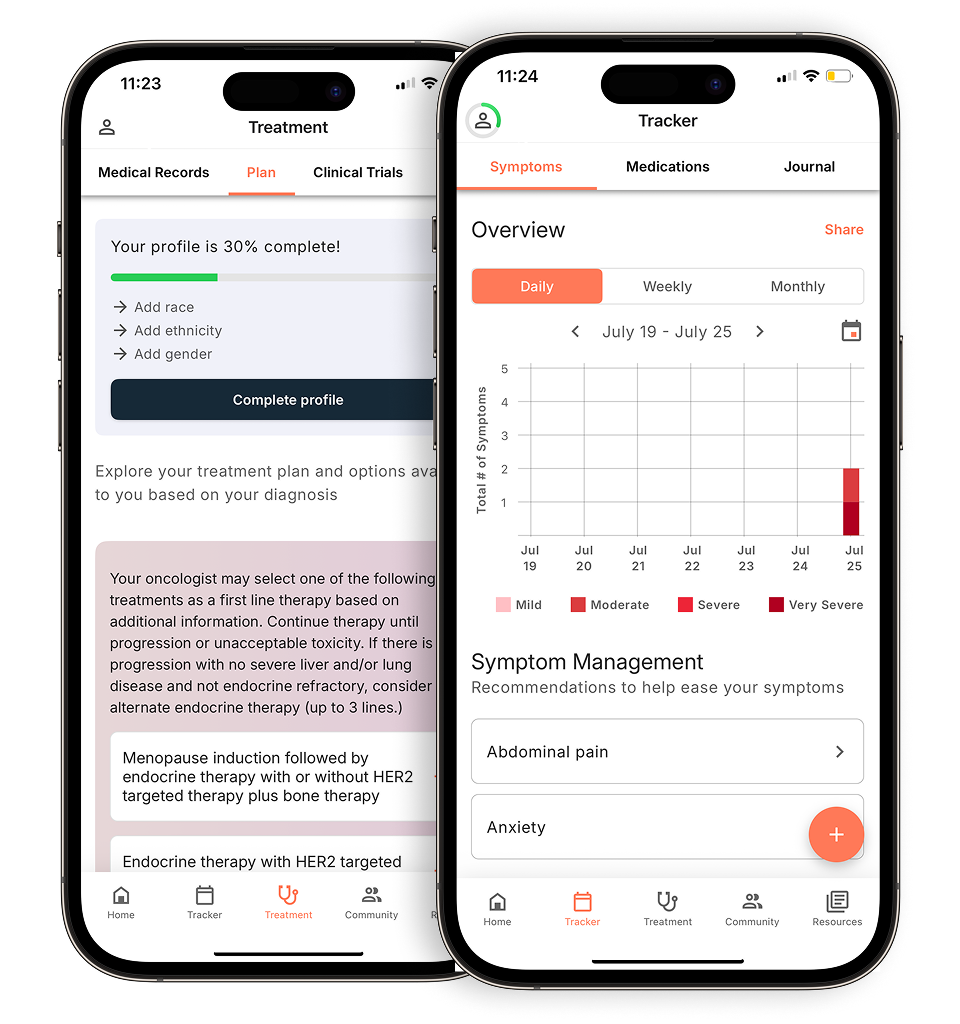

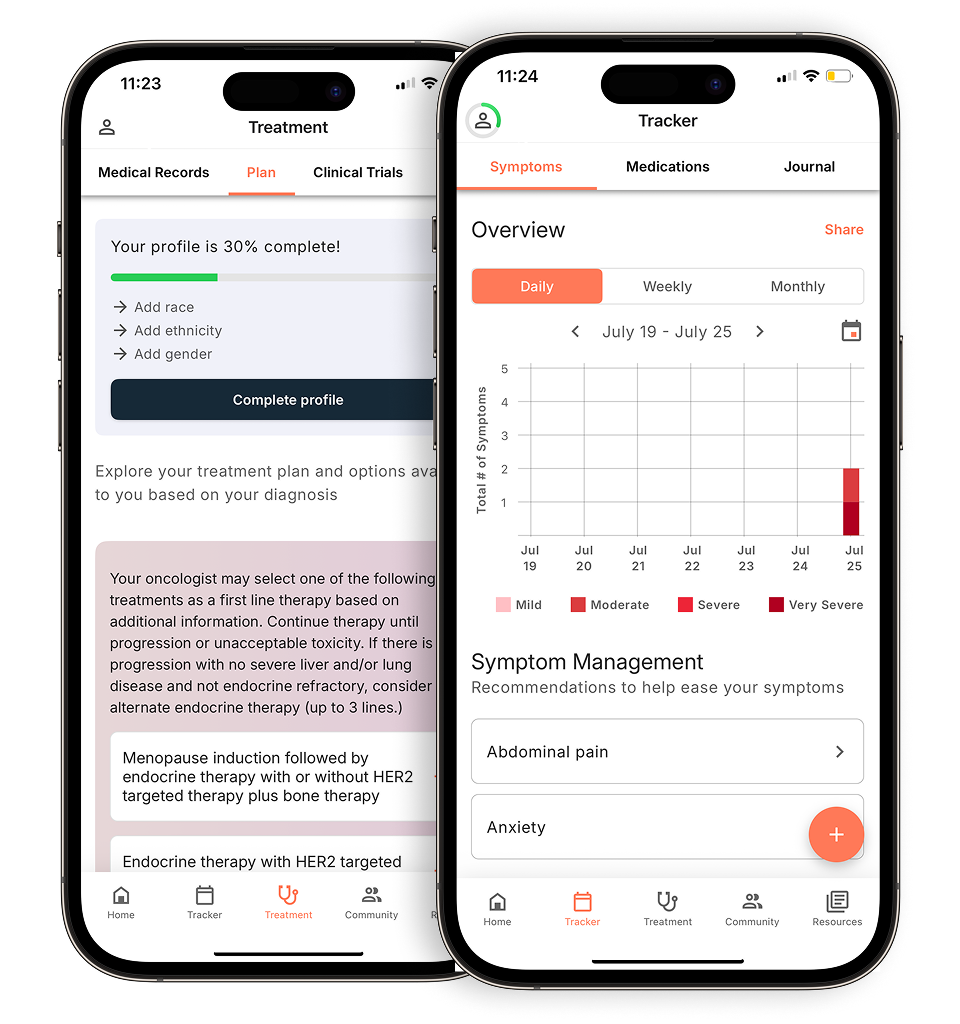

Evidence-based guidance powered by NCCN Guidelines®

Personalized treatment plans shaped by the latest oncology standards—tailored to your diagnosis.

Get started

View your personalized treatment plan in the Outcomes4Me app

Use your diagnosis to unlock personalized NCCN Guidelines®-aligned recommendations.

Continue in app

When bladder cancer grows into the bladder’s muscle wall, that’s a different story. That type of cancer tends to spread. It’s “on the move,” not staying confined to the surface. For muscle-invasive bladder cancer that hasn’t spread widely, we treat it with systemic therapy. What we used to simply call chemotherapy, though now it may involve other targeted or immunotherapies. These treatments circulate throughout the body to kill cancer cells wherever they may be hiding. After that, patients often undergo surgery or radiation. In some cases, if systemic therapy appears curative, we can even observe the bladder without needing to remove it.

Some patients, either from the start or after earlier treatments, come to us with cancer that has already spread to organs outside the bladder. Once that happens, it’s technically not curable, but the good news is that we now have very effective treatments that can help people live for many years. It’s an area with a lot of exciting new research.

2) How is bladder cancer typically diagnosed?

Dr. Plimack: The vast majority of patients come to us because they notice blood in their urine. That’s the most common symptom. Thankfully, bladder cancer often does present with a symptom, unlike some cancers that grow quietly for a long time. I always tell people: If you see blood in your urine, it’s never normal. You need to get it checked out.

The best way to evaluate this is with a cystoscopy, where a urologist looks directly inside the bladder to check for tumors. That accounts for most of the cases we diagnose.

For muscle-invasive cancer, we image the chest, abdomen, and pelvis to check whether it has spread. For non–muscle invasive cancer, imaging is usually limited to the bladder area, since we don’t expect it to have spread. In metastatic disease, where there are tumor deposits outside the bladder, imaging is essential to monitor those areas and make sure they’re responding to treatment.

3) Can you explain staging and grade?

Dr. Plimack: Let’s start with grade. Bladder cancer is diagnosed from a sample of cancer cells—usually removed during a cystoscopic biopsy called a TURBT (transurethral resection of bladder tumor), or sometimes from urine cytology. A pathologist looks at the cells and determines whether they’re low-grade or high-grade. High-grade tumors are more likely to spread; low-grade tumors usually stay on the bladder surface. Grade gives us our first clue about the biology of the cancer.

As for staging, it’s more technical and matters most when we’re considering surgery. All patients with metastatic disease are considered stage IV, but that term can mean very different things. People often hear “stage IV” and think it’s automatically a death sentence, and that’s simply not true.

When I talk to patients, I try to move away from stage numbers and focus more on whether the cancer is confined, whether it has spread, whether it’s curable, and what our treatment options are.

That said, staging loosely breaks down like this:

- Stage I or below: non–muscle invasive

- Stage II: muscle-invasive

- Stage III: advanced local invasion

- Stage IV: spread to distant organs or nearby structures

Again, the more meaningful conversation is about what your specific cancer looks like and what that means for treatment.

4) How do you decide between bladder preservation and bladder removal (cystectomy)?

Dr. Plimack: That’s a really important and complex decision. Bladder surgery is a major operation. For men, removing the bladder includes removing the prostate and lymph nodes. For women, it usually involves removing the bladder along with the uterus and ovaries.

Afterward, the urine needs a new place to go. That might be:

- an ileal conduit, where urine drains into an external ostomy bag, or

- a continent diversion, where urine is stored inside the body and drained either by catheter or through a reconstructed urinary pathway, like a neobladder.

Because the surgery is lengthy and involves reconstruction, you need a highly skilled surgeon. The decision to remove the bladder depends on several factors. One is how well the bladder is functioning—some bladders are already leaking, blocked, or requiring nephrostomy tubes, making removal more appropriate.

Another factor is the cancer itself. For non–muscle invasive cancer, we can often preserve the bladder with treatments placed directly into it. These treatments require frequent visits, ongoing surveillance, and they carry some risk of progression. They can also sometimes damage the bladder over time.

For muscle-invasive bladder cancer, we typically consider bladder removal—but only after giving neoadjuvant therapy to shrink the tumor and eliminate any microscopic spread.

Radiation is another bladder-preserving option, but it’s suitable for a smaller group of patients. The cancer has to be confined to the bladder (not the lymph nodes, not extending beyond the bladder wall), and the bladder must be healthy enough to function after radiation. When it works, it can be curative, though most commonly we use it in older patients because once a bladder is radiated, surgery later becomes much more difficult.

Watch the full episode with Dr. Plimack here.

Personalized support for real care decisions

Understand your diagnosis, explore clinical trials, and track symptoms--all in one place.

Get started

Compare treatments, prepare for appointments, and track side effects—all in the app

Built for your diagnosis, Outcomes4Me gives you the tools to make confident, informed decisions—right when you need them.

Continue in app