Dr. Stephen V. Liu, a thoracic oncologist at Georgetown University’s Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center, explains how targeted therapy is transforming the way care teams are treating non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Unlike traditional chemotherapy and radiation therapy, targeted therapies focus on specific genetic changes that drive cancer growth. In this recap from Chapter One of our “Precision Minute” series, Dr. Liu explains the science behind targeted therapies and how they’re shaping the world of personalized medicine.

Transcript

The transcript has been edited for clarity and conciseness.

What does targeted therapy for NSCLC mean?

Dr. Stephen V. Liu: Targeted therapy can mean a lot of different things. In general, we’re talking about a cancer treatment that uses medicines, drugs, or anti-cancer agents to attack some molecule unique to the cancer cell.

When we think of historic treatments for cancer, agents like cytotoxic chemotherapy or radiation, these are treatments that attack cells that are growing quickly, which cancer cells do. However, there are many normal cells that also grow quickly and those are responsible for a lot of the side effects with those treatments.

Targeted therapy really tries to leverage something unique to the cancer: a protein that’s expressed on the cancer cell but not on a normal cell, or something that is overactive in a cancer cell, or something that the cancer cell relies on that a normal cell doesn’t.

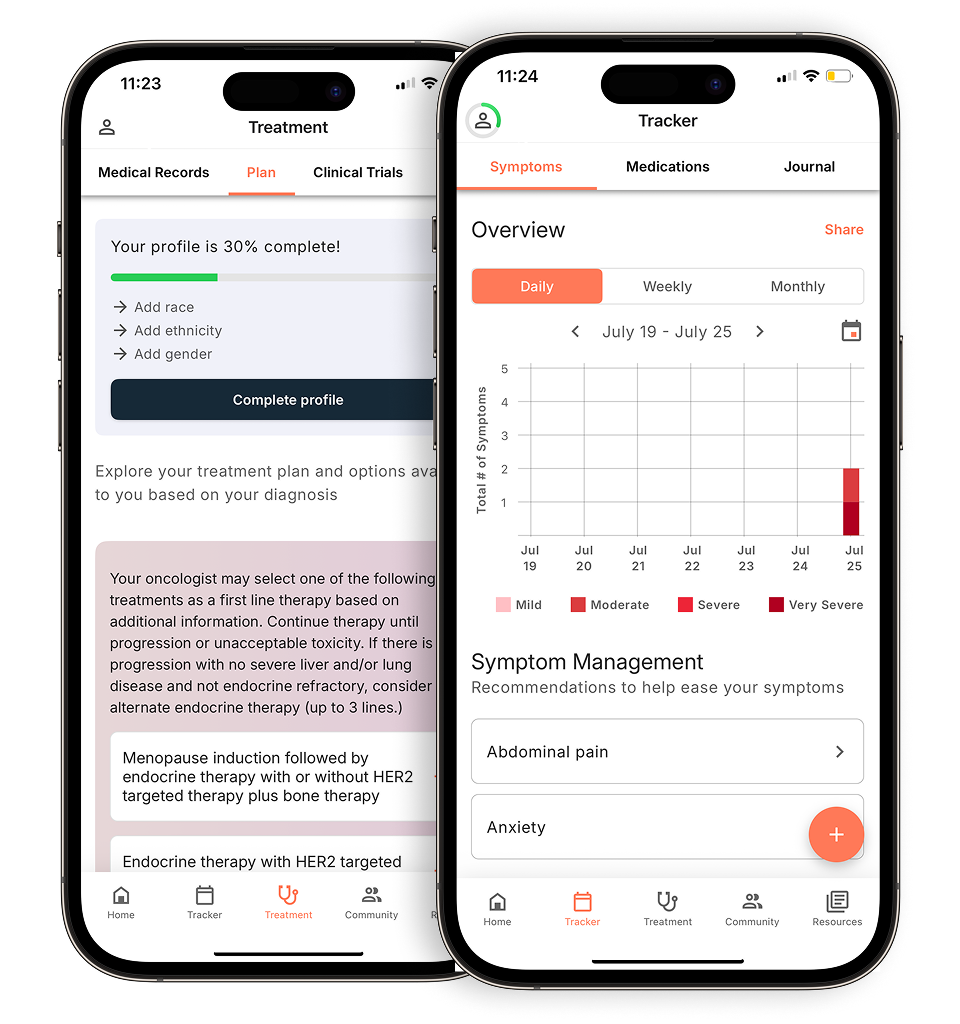

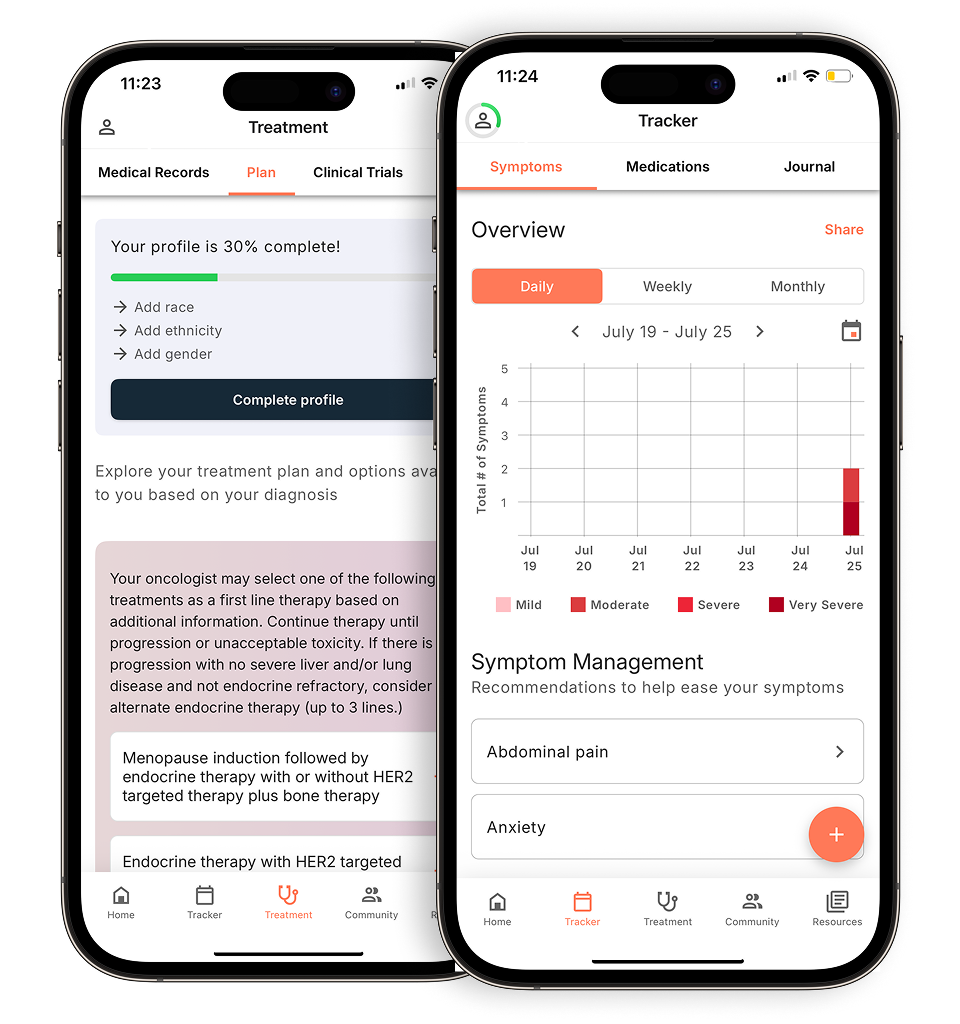

Evidence-based guidance powered by NCCN Guidelines®

Personalized treatment plans shaped by the latest oncology standards—tailored to your diagnosis.

Get started

View your personalized treatment plan in the Outcomes4Me app

Use your diagnosis to unlock personalized NCCN Guidelines®-aligned recommendations.

Continue in app

So that when we target that specific molecule, when we take that molecule away, it will disproportionately affect the cancer cell and spare the normal cell. In theory, a targeted agent should have a very high chance of success with very few side effects. There are some targeted agents that are more successful at that than others. What we’re looking for is something unique to the cancer.

Fighting a cancer cell is different than fighting an infection. An infection is a foreign body; it doesn’t belong there. Our body recognizes that it’s foreign, but every cancer cell starts off as a normal cell. So when we’re trying to attack that cancer cell, we have to be careful that the part of the cell we’re attacking won’t affect all of our normal cells as well. Otherwise, that treatment will have far too many side effects.

When we look at non-small cell lung cancer, we know that this is a genetic disease. In most cases, it’s not something we inherit from our parents or pass on to our children. It’s the result of changes to our genetic material, changes to our DNA, that we acquire through some exposure, whether it’s cigarette smoke, radon, pollution, or something we don’t even recognize yet.

So, the DNA changes. It changes in a way that causes the cell to grow uncontrollably and move around when it shouldn’t. The change in the DNA changes the behavior of that cell and turns it from a normal lung cell into a lung cancer. If we can pinpoint exactly what that change is, we can try to develop drugs that target that specific change. This would be genomic testing, where we take the tumor cell, we look at its DNA and RNA, and try to isolate what’s different. What are the specific changes unique to this cancer?

I think a good example would be ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase. When we see a chromosomal rearrangement or a gene fusion (same thing in the ALK gene), it results in a cell that is growing uncontrollably and surviving longer than it should. This protein is expressed on these cancer cells and gives them a survival advantage.

Our chemists can now develop medicines that block the function of that protein, cut that wire, and stop that signaling from happening, so when the cell is relying on ALK to survive, we can deliver a medicine that blocks ALK.

Those cancer cells will die, and because our normal cells aren’t so reliant on ALK, it’ll spare our normal cells. The result is medicines that work for almost everybody when that ALK fusion is present, and will have relatively few side effects. If that ALK protein is not present, that drug won’t do anything.

That’s why we need to do that testing, to really isolate what the specific changes are in this particular cancer. If we see that ALK fusion or overexpression of the ALK protein, we know an ALK inhibitor is the right treatment. Not an option for treatment, the right treatment.

The same holds true for ROS1. ROS1 fusions are a little less common than ALK, but follow the same principle. When that ROS1 fusion is present, we want to deliver a medicine that’s going to block that ROS1 signal. It’ll have very few consequences in terms of our normal body and side effects, and be devastating for the cancer that relies on that ROS1 signal.

So, that’s targeted therapy. There’s a lot of nuance in developing newer and better targeted therapies, but generally, we want a medicine that is going to affect the cancer cell and leave our normal body alone.

Learn more about ALK+ and ROS1 NSCLC from Dr. Liu in the full video here.

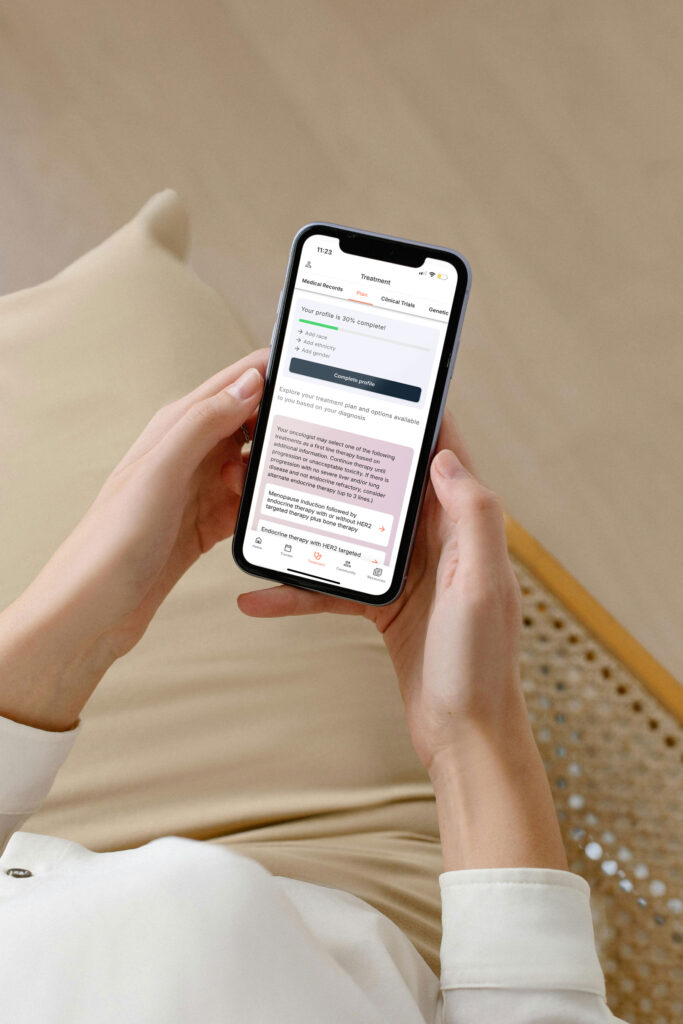

Personalized support for real care decisions

Understand your diagnosis, explore clinical trials, and track symptoms--all in one place.

Get started

Compare treatments, prepare for appointments, and track side effects—all in the app

Built for your diagnosis, Outcomes4Me gives you the tools to make confident, informed decisions—right when you need them.

Continue in app