A pathology report is one of the first pieces of information you’ll receive after a breast cancer diagnosis. It’s packed with medical language that can be hard to make sense of on your own, but understanding the basics can help you feel more in control. Breast medical oncologist Dr. Pooja Advani walks through the key elements your doctor looks at, what they mean, and how they shape your treatment plan in this Q&A.

The following questions and responses have been lightly edited for grammatical purposes.

1) What are some things to look out for in a pathology report after a breast cancer diagnosis?

One of the first things patients can look for in their pathology report is whether it mentions invasive carcinoma. Sometimes the report may instead say carcinoma in situ, and in some cases, it may list both.

The most important difference between carcinoma in situ and invasive carcinoma, and what I often explain to patients, is that they exist along the same spectrum. Carcinoma in situ can transform into invasive carcinoma over time. Carcinoma in situ means the cancerous cells are growing but remain contained within the milk duct. Ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) is the most common form. When the report mentions invasive ductal carcinoma, it means those cancerous cells have broken through the lining of the milk duct. In both situations, the cancer is still contained within the breast.

First, your pathology report will typically note whether you have invasive ductal carcinoma, ductal carcinoma in situ, or both. When both are present, we generally treat it as invasive ductal carcinoma, because that is the more aggressive of the two.

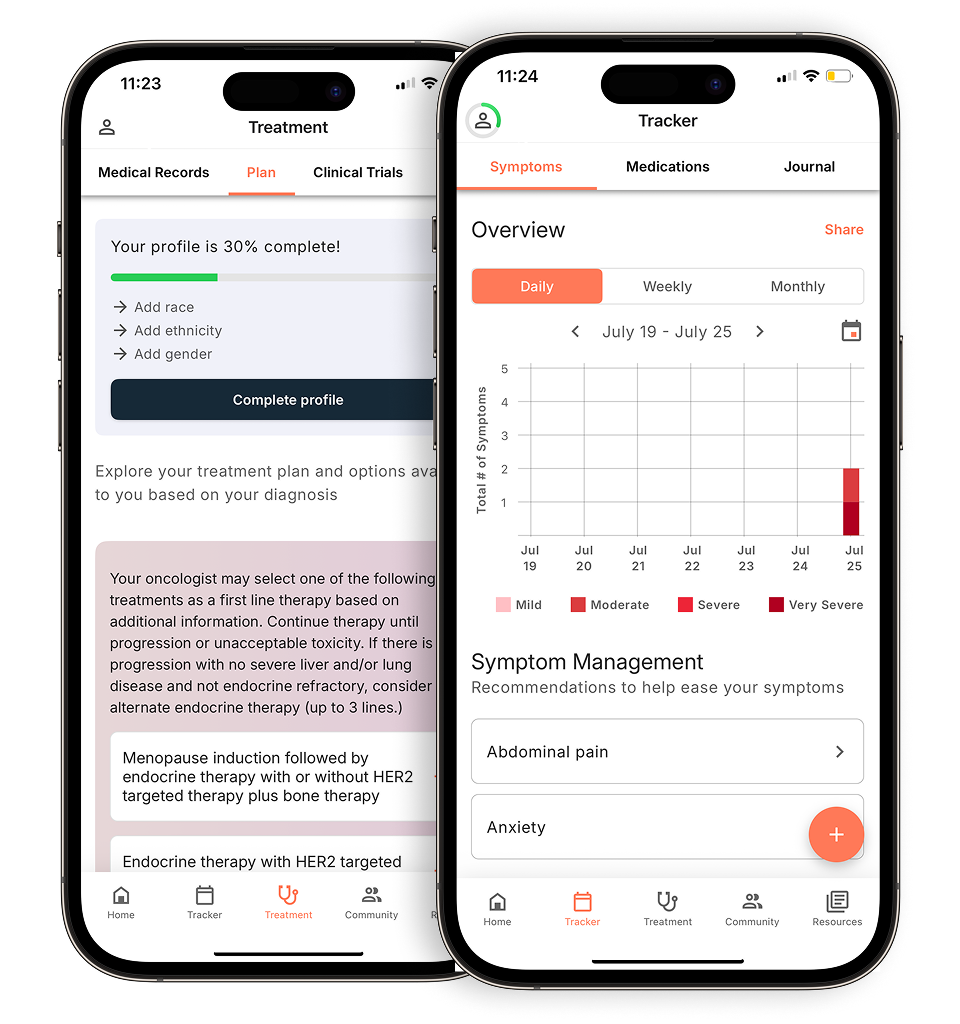

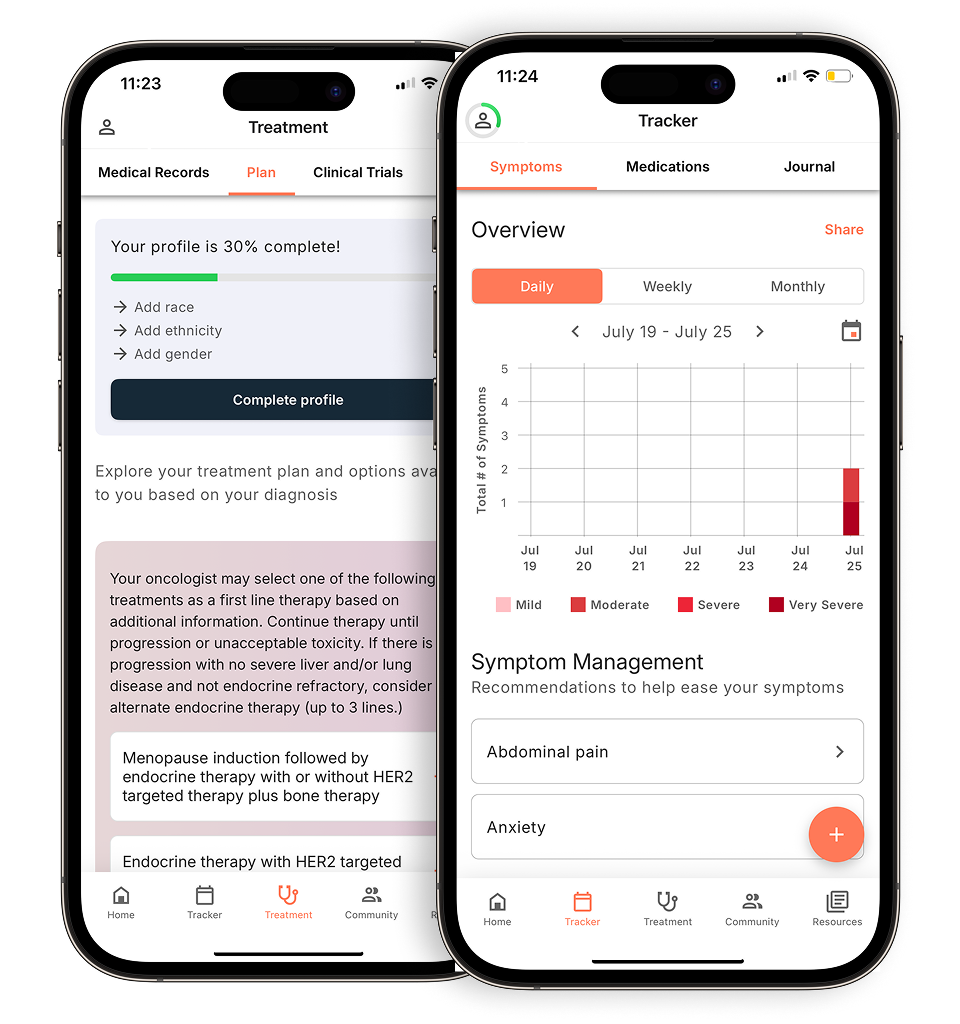

Evidence-based guidance powered by NCCN Guidelines®

Personalized treatment plans shaped by the latest oncology standards—tailored to your diagnosis.

Get started

View your personalized treatment plan in the Outcomes4Me app

Use your diagnosis to unlock personalized NCCN Guidelines®-aligned recommendations.

Continue in app

The second key component is the grade, which is different from the stage. Grade is one factor used in determining stage, but the two are distinct. Tumors are graded on a scale of 1, 2, or 3. When the pathologist looks at the sample under the microscope, they’re assessing how similar or how different the cancer cells are compared to normal breast cells.

If the cells still look fairly similar to normal breast tissue, that’s grade 1. If they look very abnormal or “poorly differentiated,” that’s grade 3. Grade 2 falls somewhere in between.

The grade gives us insight into the tumor’s biological behavior and helps inform treatment decisions.

Next, we look at the receptors, and there are three:

- Estrogen receptor (ER)

- Progesterone receptor (PR)

- HER2 receptor

I often tell patients to think of receptors like docking stations, just like a boat docks at a port. Estrogen, for example, binds to the estrogen receptor, becomes activated, and then sends signals to the cells to grow and divide. What we’re trying to understand is: What is feeding this cancer?

About 70% of breast cancers are hormone receptor–positive, meaning they express estrogen and progesterone receptors and are typically fueled by hormones. About 15–20% are HER2-positive, meaning the HER2 receptor is overexpressed; this is important because we now have targeted therapies specifically for HER2-positive disease.

If a tumor is negative for all three receptors (ER, PR, and HER2), we call that triple-negative breast cancer, which tends to behave more aggressively and is more commonly seen in African American patients.

Those are the main components patients will see in the pathology report, but it’s always helpful to review the details with your care team.

2) Why do some patients see a surgical oncologist before a medical oncologist?

Every institution handles the process a little differently. Many cancer centers start with the surgeon. At our center, patients first meet with a breast medicine specialist and a nurse navigator. Their role is to educate patients, gather all relevant medical information (especially if the diagnosis was made outside our system), and order any needed tests, like a breast MRI, PET scan, blood work, or an echocardiogram, so the patient is fully prepared for their visit with the medical oncologist or surgeon.

Whether a patient sees the surgeon first or the medical oncologist first often depends on the cancer subtype and clinical stage. Clinical stage is based on tumor size (from imaging or physical exam) and whether lymph nodes appear positive.

For patients with triple-negative or HER2-positive breast cancer, especially those with tumors larger than 2 centimeters or with lymph node involvement, we usually prioritize seeing the medical oncologist first. These patients often benefit from starting treatment before surgery, such as chemotherapy, immunotherapy, or HER2-targeted therapy. This approach is called neoadjuvant therapy.

When it’s not clear what the best first step is, most practices will have the patient start with the surgeon, who can help determine the clinical stage and guide next steps.

Patients who have surgery first, whether a lumpectomy or mastectomy, are typically referred afterward to medical oncology and radiation oncology, workflows vary by institution.

3) What’s the difference between the clinical stage and the pathologic stage?

The difference between clinical stage and pathologic stage is another important point. Clinical stage is assigned at diagnosis and is based on tumor size, lymph node status, and sometimes additional imaging to rule out distant metastases. We use the TNM system (tumor, lymph nodes, metastasis). Grade and receptor status are also factored in.

Surgery gives us the most definitive information. After removing the tumor, the pathologist examines the full specimen. They measure the true tumor size, assess the margins (negative or positive), and evaluate lymph nodes. Most patients who appear to have negative lymph nodes clinically will have a sentinel lymph node biopsy during surgery to check for microscopic spread.

All this information, final tumor size, margin status, lymph node involvement, grade, and receptor status, is then used to determine the pathologic stage. Sometimes, the pathologic stage ends up being different from the clinical stage.

I often tell patients that clinical staging is like watching the movie trailer. Helpful, but not the full picture. Pathologic staging is the full movie. It gives us the most complete understanding of the tumor and its behavior.

Assumptions made from the initial biopsy or imaging can shift once we have the full pathology after surgery. It’s an important reminder to stay flexible during the weeks or months it takes to reach that final, most accurate diagnosis.

View part one of our recap here, where Dr. Advani shares her insights on second opinions, breast cancer misconceptions, and more.

Personalized support for real care decisions

Understand your diagnosis, explore clinical trials, and track symptoms--all in one place.

Get started

Compare treatments, prepare for appointments, and track side effects—all in the app

Built for your diagnosis, Outcomes4Me gives you the tools to make confident, informed decisions—right when you need them.

Continue in app