In this final “Ask the Webinar” recap, Dr. Charles Rudin, a leading lung cancer specialist and Deputy Director of the Cancer Center at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, answered patient questions on recurrence, clinical trials, and new therapies for small-cell lung cancer (SCLC).

Whether you’re navigating treatment decisions or trying to balance quality of life, this section highlights what patients need to know and what researchers are actively working on.

The following questions and responses have been lightly edited for grammatical purposes.

1) How long does it typically take for SCLC to come back, and what’s the best way to monitor for recurrence?

Dr. Rudin: It’s really variable. Some patients have a long duration of response, and others can progress pretty quickly. Typically, most patients see recurrence within the first six months after chemotherapy. After that, the probability of recurrence starts to go down. The longer you’re out without recurrence, the more likely things will look okay on the next scan.

We tell patients that this is a serious and potentially fatal disease, so we’re going to watch closely and try to treat it quickly if it comes back. Usually, in that first year, we scan about every three months. After a year, we might space scans out a bit to reduce radiation exposure. I worry more about the disease coming back than the radiation. especially with SCLC.

2) Are there any promising new therapies for relapsed SCLC?

Dr. Rudin: Yes, there are. We talked about tarlatamab, which is one of a whole group of drugs we call T-cell engagers. There are several others being studied in active clinical trials.

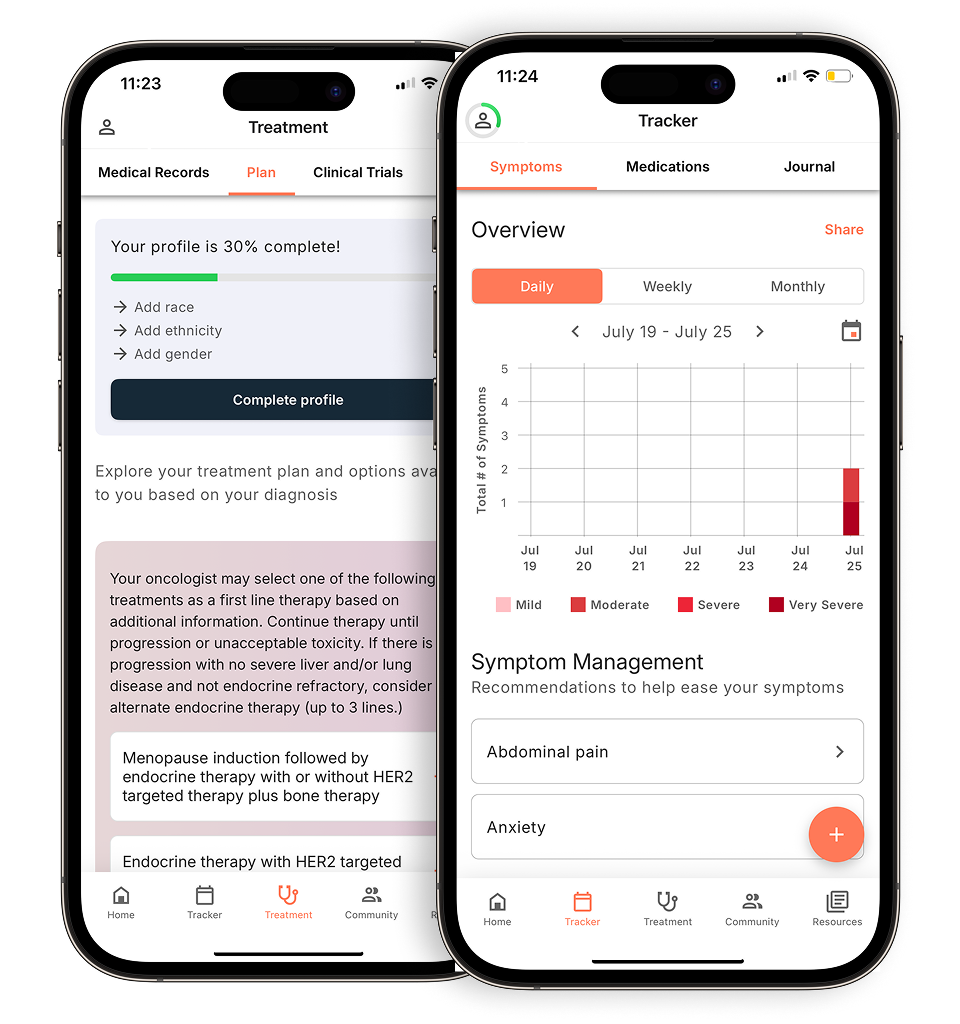

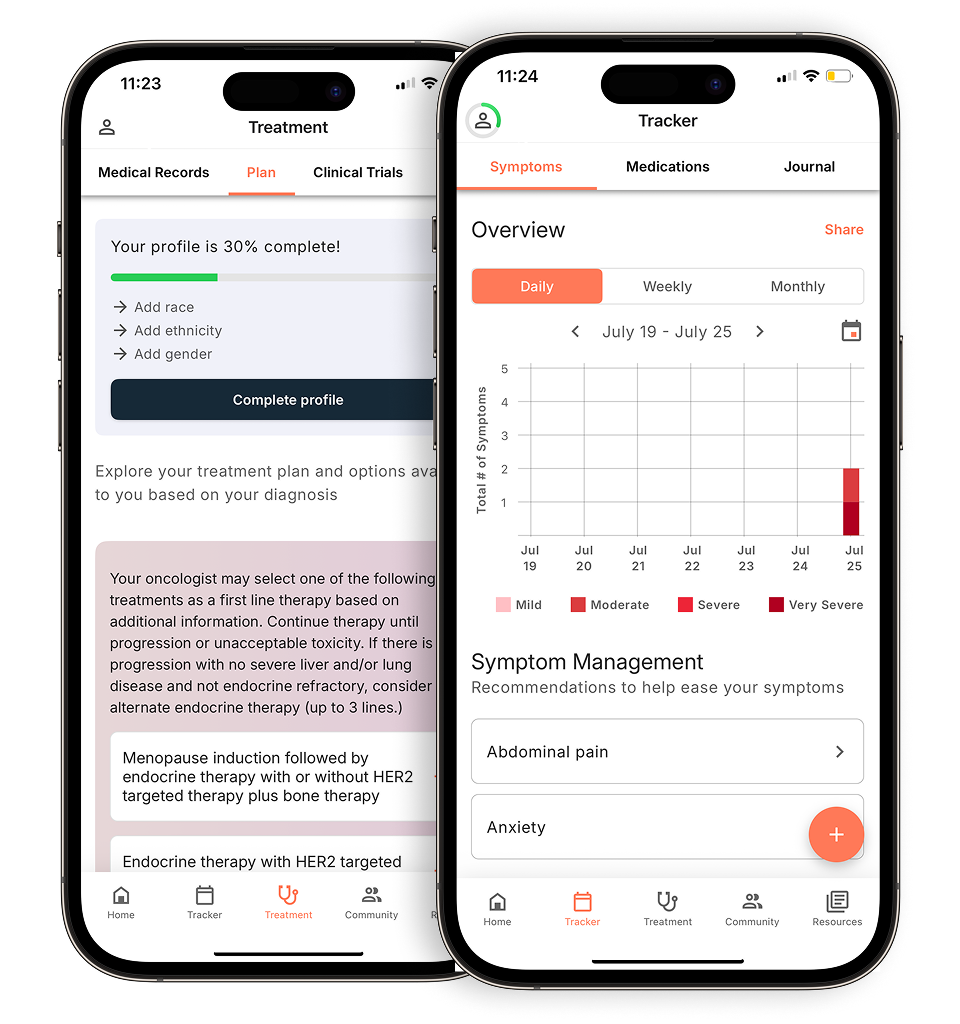

Evidence-based guidance powered by NCCN Guidelines®

Personalized treatment plans shaped by the latest oncology standards—tailored to your diagnosis.

Get started

View your personalized treatment plan in the Outcomes4Me app

Use your diagnosis to unlock personalized NCCN Guidelines®-aligned recommendations.

Continue in app

Another exciting area is antibody-drug conjugates. These are antibodies that target the cancer cell but are linked to a chemotherapy drug, kind of like a Trojan horse. A couple of these have shown really good activity in patients, with high response rates, although the durability isn’t always as long as we’d like. Right now, research is focused on how to combine these therapies, T-cell engagers with antibody-drug conjugates, to try to get more durable responses.

This is really exciting. Historically, this has been an area with limited options, and now there are a lot of drugs showing activity. As a researcher, it’s gratifying to see so much happening.

3) How can patients find clinical trials for SCLC?

Dr. Rudin: There are a few places to look. LUNGevity is a patient-oriented site. The Lung Cancer Research Foundation is another. These sites give info on the disease and ongoing trials. ClinicalTrials.gov is useful too, but it can be tricky for patients to navigate.

The best approach is to talk with your doctor. They can help identify referral centers or investigational therapies that might fit your case.

4) Are there telemedicine trials for patients who live far from major cancer centers?

Dr. Rudin: That’s always a challenge. Telemedicine has become more common, which is great for patients. But distributed or community-based trials are still in early stages. At Sloan Kettering, we’re exploring some of this, but for SCLC, fully virtual trials aren’t widely available yet. It’s clearly a need, and there are people working on virtual trials to make them more accessible.

5) How do you help patients balance aggressive treatment versus quality of life when the prognosis is uncertain?

Dr. Rudin: Super important issue. This is something where the discussion with the clinician, the family, and the patient really comes into play. There’s no single right answer. We’re all interested in survival, but we’re also all interested in quality of life.

The balance is really hard to strike, and honestly, different patients have different thresholds for what they’re willing to trade on one side of that equation versus the other. It’s an ongoing conversation we have at every clinic visit, checking in, seeing how the patient is doing, figuring out: Do we want to push forward? Do we want to pull back? What’s the balance of risks and benefits?

I think the goal is to give people duration of survival, but also good quality of life for that survival. There’s no sense in having a long period of days that are miserable. Focusing on quality of life is really central to oncology care in general.

6) What signs should I watch for that might indicate disease progression or a need to adjust treatment?

Dr. Rudin: Besides scans, pay attention to how you feel. If you’re losing weight, feeling worse, or your functional status drops, those are reasons to check in sooner. Things like new pain, shortness of breath, or coughing up blood are reasons to scan earlier and see if therapy needs to change.

7) Are there therapies or trials aimed at preventing small-cell transformation?

Dr. Rudin: Some tumors start as lung adenocarcinoma and can “transform” into small-cell as a resistance mechanism. We’re really interested in figuring out how to prevent that. Our lab is studying it closely, but we haven’t cracked it yet. Right now, we treat transformed small-cell like primary small-cell. There’s a lot of new biology coming out, and I’m hopeful that in the next few years, we’ll have more targeted therapies for these patients.

8) Are trials appropriate if I’m still thought of as curative versus palliative?

Dr. Rudin: Absolutely. We have clinical trials for patients who we think might have potentially curable disease. We also have trials for patients with advanced disease, where cure isn’t really expected, but the goal is to improve the duration of survival and quality of life. Both situations are really important and pretty common, and we need better therapies for both. So yes, trials can be appropriate in either scenario.

9) How many chemotherapy sessions are recommended?

Dr. Rudin: There’s no minimum. If chemo is intolerable, more isn’t better. For first-line treatment, we usually aim for four cycles. The data show six isn’t better than four, and eight isn’t better than six. You get your best response in the first few cycles. For recurrent disease, the approach depends on tolerance and benefit, sometimes we continue if the patient is doing well and responding.

View our previous recaps from Dr. Rudin or watch the full webinar replay here.

Personalized support for real care decisions

Understand your diagnosis, explore clinical trials, and track symptoms--all in one place.

Get started

Compare treatments, prepare for appointments, and track side effects—all in the app

Built for your diagnosis, Outcomes4Me gives you the tools to make confident, informed decisions—right when you need them.

Continue in app