In our recent “Ask the Expert” webinar, we had the privilege of speaking with Dr. Charles Rudin, a leading thoracic oncologist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and a renowned lung cancer expert.

In part two of our discussion, Dr. Rudin answers some of the most common questions patients have about chemotherapy, immunotherapy, recurrence, and what to expect throughout treatment for small-cell lung cancer (SCLC). You can also view the full webinar replay, below.

The following questions and responses have been lightly edited for grammatical purposes.

For many patients, understanding how to manage cancer treatment symptoms—such as fatigue, autoimmune side effects, and quality-of-life changes—is just as important as knowing how well the treatment is controlling the disease.

1) If a patient is being treated with chemotherapy plus immunotherapy, how do you know if the immunotherapy is working or if it’s mostly the chemotherapy?

Dr. Rudin: Early on, SCLC is very chemotherapy-responsive. We often see a pretty dramatic shrinkage of tumors with chemotherapy alone.

When you give chemo-immunotherapy together, it can be hard to know whether the tumor is shrinking mainly because of the chemotherapy or if the immunotherapy is contributing.

The way we really know immunotherapy is playing an important role is in the longer-term survivors. Initially, we see good responses with chemotherapy alone or with chemo-immunotherapy, and that initial treatment period is only about three to three and a half months.

After that, patients stay on what we call maintenance immunotherapy, meaning just immunotherapy. Historically, before immunotherapy existed, survival curves dropped off sharply at that point. There were almost no long-term survivors. Now, those curves have a “tail,” meaning some patients are living much longer.

Over time, if someone remains free of disease progression for many months, that’s when we know the immunotherapy is really benefiting them. Historically, those patients wouldn’t have made it that far.

2) Is PD-L1 testing helpful for determining whether immunotherapy would work?

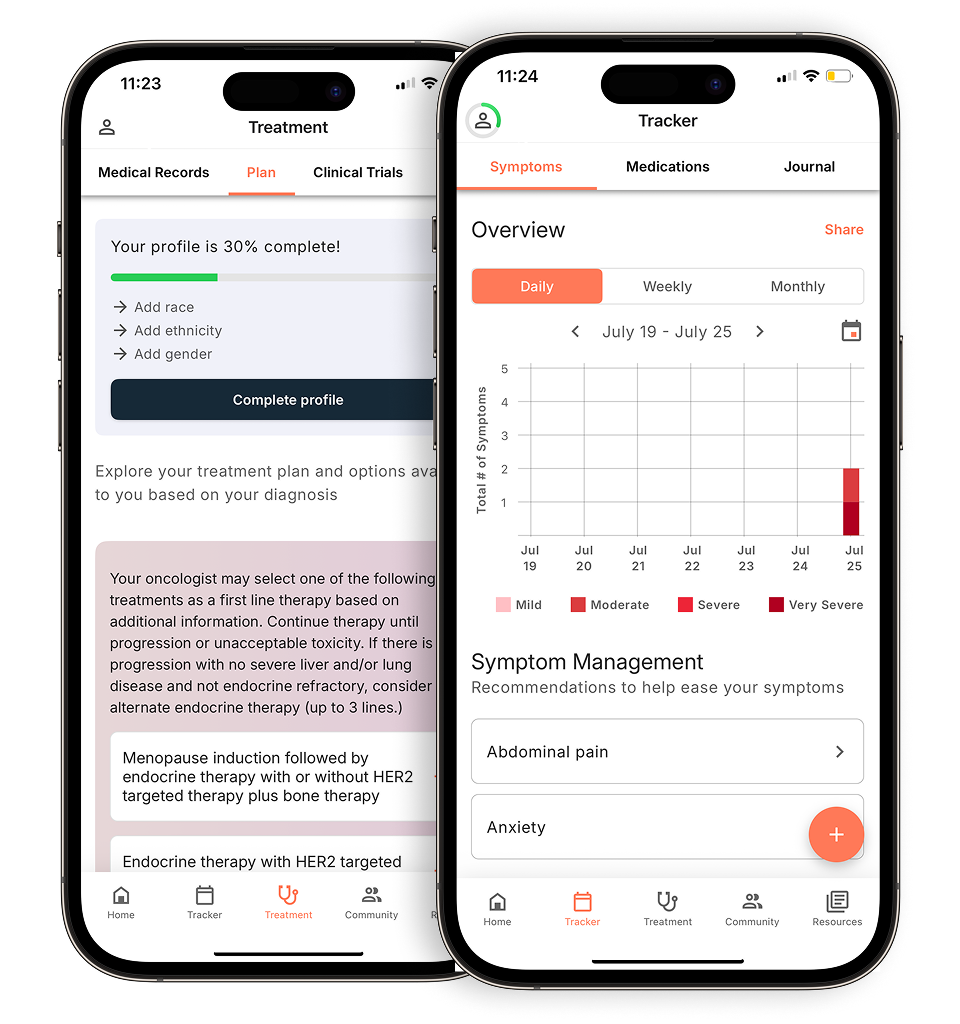

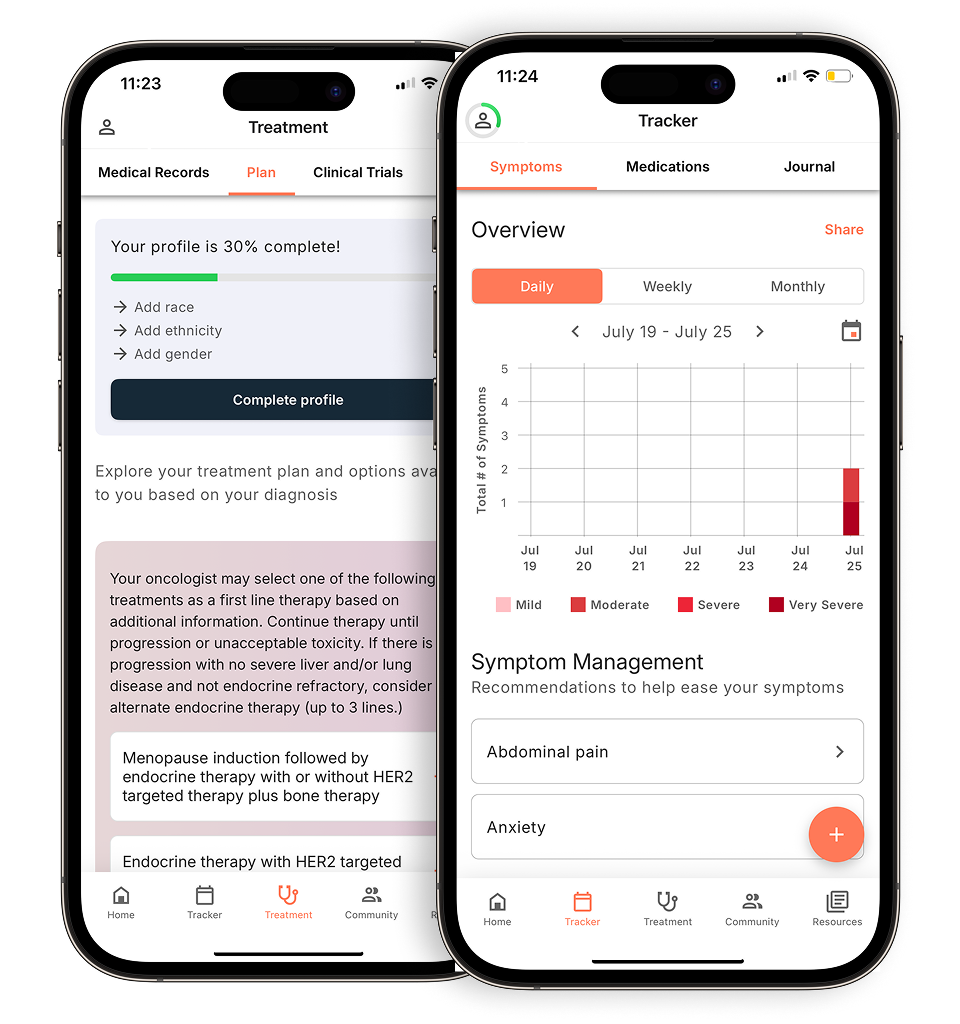

Evidence-based guidance powered by NCCN Guidelines®

Personalized treatment plans shaped by the latest oncology standards—tailored to your diagnosis.

Get started

View your personalized treatment plan in the Outcomes4Me app

Use your diagnosis to unlock personalized NCCN Guidelines®-aligned recommendations.

Continue in app

Dr. Rudin: PD-L1 is not a useful marker in SCLC. It’s usually low and doesn’t correlate with immunotherapy benefit.

There are certain patients who shouldn’t get immunotherapy, specifically those with significant underlying autoimmune diseases, like lupus, where treatment could worsen their condition. But the vast majority of patients with SCLC are eligible for immunotherapy and, frankly, should receive it if possible.

3) For people who have finished first-line therapy, what’s the thinking around maintenance therapy? Should they continue immunotherapy?

Dr. Rudin: Continuing immunotherapy is the standard of care. The trials that redefined first-line treatment (chemo plus immunotherapy) all included maintenance immunotherapy. We don’t have a control group without it, but we believe continuing immunotherapy alone after chemo is an important part of treatment.

4) I tolerated chemotherapy fairly well, but had a hard time with immunotherapy side effects. Are there alternatives for patients who can’t handle immunotherapy? What are the most common side effects?

Dr. Rudin: We tend to think of immunotherapy as being gentler than chemotherapy, but it absolutely has its own toxicities. The side effects come from taking the brakes off the immune system. It can start attacking normal tissues, not just the cancer.

Some of the autoimmune side effects we see include:

- Colitis (inflammation of the colon), causing diarrhea

- Autoimmune thyroiditis, leading to permanent loss of thyroid function

- Pneumonitis (inflammation in the lungs), rare but can be serious or even fatal

- Dermatitis or rashes

When we see autoimmune pneumonitis, we stop immunotherapy because it’s not safe to continue. Many other side effects can be managed. Stopping treatment temporarily, giving steroids, and calming down the immune system often helps.

If a patient permanently loses thyroid function, it can be replaced with daily thyroid hormone.

For patients with very significant immunotherapy toxicity, we focus on treating the side effects. If immunotherapy needs to be stopped, it doesn’t mean all benefit is lost. Interestingly, patients who experience immune-related side effects are often more likely to have meaningful cancer control. It’s a good news/bad news situation. Even if immunotherapy must be discontinued, there’s still reason to be hopeful.

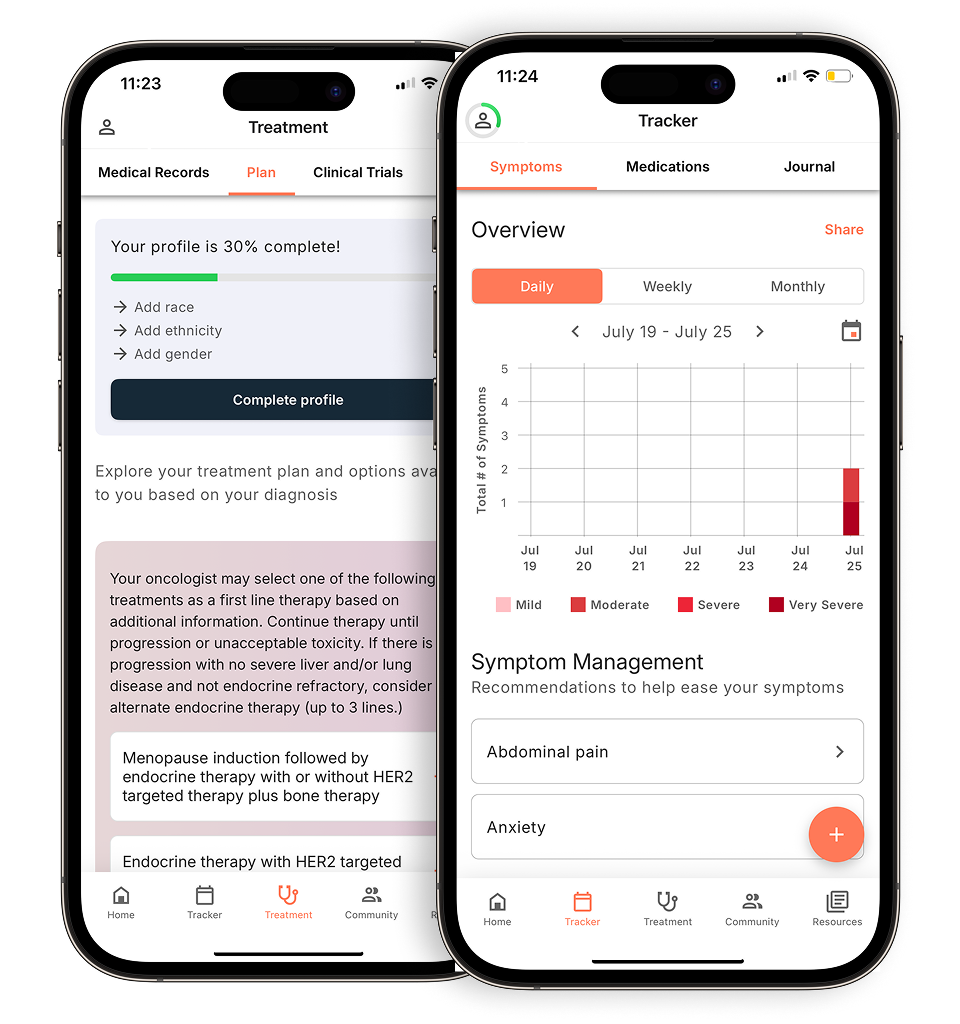

Cancer care guidance for every step of your journey

Get treatment options, clinical trials, and support tailored to your diagnosis--all in one place.

Get started

See treatment options, manage symptoms, and stay informed—all in the app

View treatment options and trials personalized to your diagnosis—plus track progress in real time.

Continue in app

5) Are there any strategies or medications to help with fatigue?

Dr. Rudin: Fatigue is extremely common, and unfortunately, we don’t have a perfect medication for it. Sometimes we give a very low dose of steroids, below the level where they would cause issues with blood sugar or sleep, to give people a little more energy.

Fatigue often improves with time, especially the further someone gets from chemotherapy.

Sometimes fatigue is related to anemia, when red blood cells and oxygen-carrying capacity drop after chemotherapy. In cases where it’s very low, a blood transfusion may help, but that’s a minority of patients.

Overall, fatigue is tough to treat, but it usually gets better gradually.

6) What is platinum-based chemotherapy, and what are its side effects?

Dr. Rudin: The standard first-line chemotherapy for SCLC, used since the 1990s, is a combination of a platinum drug (cisplatin or carboplatin) with a second drug called etoposide.

These are traditional chemotherapy drugs that kill rapidly dividing cells. SCLC grows very fast, so it responds well.

The side effects of chemotherapy are mostly related to how these drugs work. Because they target rapidly dividing cells, they don’t just affect cancer cells, they also impact normal cells in the body that divide quickly. This includes your blood cells, so we often see anemia and a drop in white blood cells, which are important for fighting infection. The gut lining also turns over quickly, which is why nausea and other gastrointestinal symptoms are common. Fatigue is frequent as well. Hair loss can happen too, because hair follicles are rapidly dividing cells.

7) If a patient was treated with platinum-based chemotherapy and the cancer came back, what are the current second-line options?

Dr. Rudin: Historically, we used more chemotherapy, but second-line chemo is less effective.

Recently, we’ve seen the emergence of a new immunotherapy strategy using T-cell engagers. One of these drugs, tarlatamab, was recently FDA-approved. It binds both the cancer cell and the T cell, bringing them together and activating the T cell to kill the tumor.

This has become a new standard of care in the U.S. for recurrent SCLC and has shown better outcomes than chemotherapy, reducing the risk of death by about 40% over time.

8) Are patients with advanced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) eligible for immunotherapy?

Dr. Rudin: Generally, yes. The physician needs to assess how severe the COPD is, but many patients with SCLC already have smoking-related lung disease like COPD.

Because immunotherapy has created a path to longer-term survival, I tend to give patients the benefit of the doubt—try immunotherapy, monitor closely, and adjust if needed. Quality of life is critical, and we can always back off treatment if necessary.

9) Can radiation be used again after recurrence?

Dr. Rudin: Yes. Radiation is very useful for treating localized problems:

- Painful bone metastases

- Lesions in weight-bearing bones that might fracture

- Spinal lesions, to prevent spinal cord compression

- Brain metastases, especially when drugs can’t cross the blood-brain barrier well

We now often use focal radiation for isolated brain metastases, which has fewer side effects than older whole-brain radiation techniques.

10) If lung cancer comes back after two years, should molecular testing be repeated? Do mutations change over time?

Dr. Rudin: Mutations can change over time, but in SCLC, the mutational profile usually doesn’t guide treatment very much. We don’t have many targeted therapies where a specific mutation determines whether a patient should get a drug.

We do still sequence tumors, because occasionally we find something actionable, and because it helps researchers understand the disease better. Over time, as treatment pressures the cancer, more mutations accumulate, but clinically, this isn’t very impactful, at least not yet. We hope it will be more meaningful by 2030.

Watch the full webinar replay here or visit part 1 of the webinar recap for an overview of SCLC.

Personalized support for real care decisions

Understand your diagnosis, explore clinical trials, and track symptoms--all in one place.

Get started

Compare treatments, prepare for appointments, and track side effects—all in the app

Built for your diagnosis, Outcomes4Me gives you the tools to make confident, informed decisions—right when you need them.

Continue in app