New research is reshaping how experts understand colorectal cancer (CRC). In this Q&A, MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Dr. Scott Kopetz highlights the latest trends, from early-onset disease to lifestyle-related findings, and explains what the growing body of data means for patients and families.

The following questions and responses have been lightly edited for grammatical purposes.

1) Can you share some of the new data that’s come out on nutrition and lifestyle choices after CRC treatment?

This year, we have some really groundbreaking research in this space.

Historically, we’ve relied on what we call epidemiology studies to understand diet, lifestyle, and other interventions. What does that mean? It means we take 1,000 patients, we ask everyone: What are you eating? How are you exercising? What else are you taking? Then, we see who recurs and who doesn’t. That doesn’t necessarily tell us that what they ate was preventing recurrence; it just gives us hints.

Going into this year, what we’ve seen is that a low-fat, low–saturated fat diet is associated with a reduced risk of CRC recurrence. Taking vitamin D or avoiding vitamin D depletion may also be associated with a lower risk. In the past, we’ve said aspirin might be associated with reduced recurrence, and exercise looked like it might be associated as well.

There’s been a lot of uncertainty. Is it that people who exercise are also the people who show up for follow-up appointments? Or that people who exercise also eat better? It’s been hard to really tease out what’s going on.

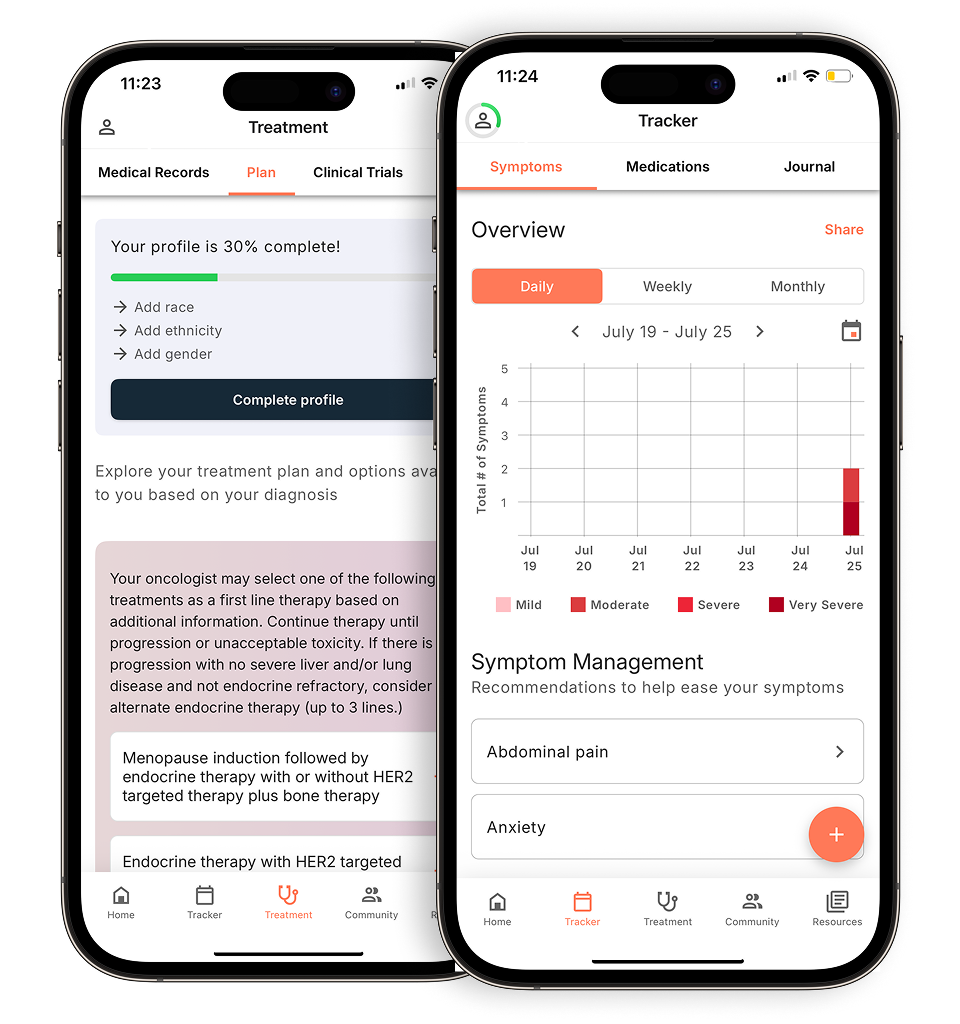

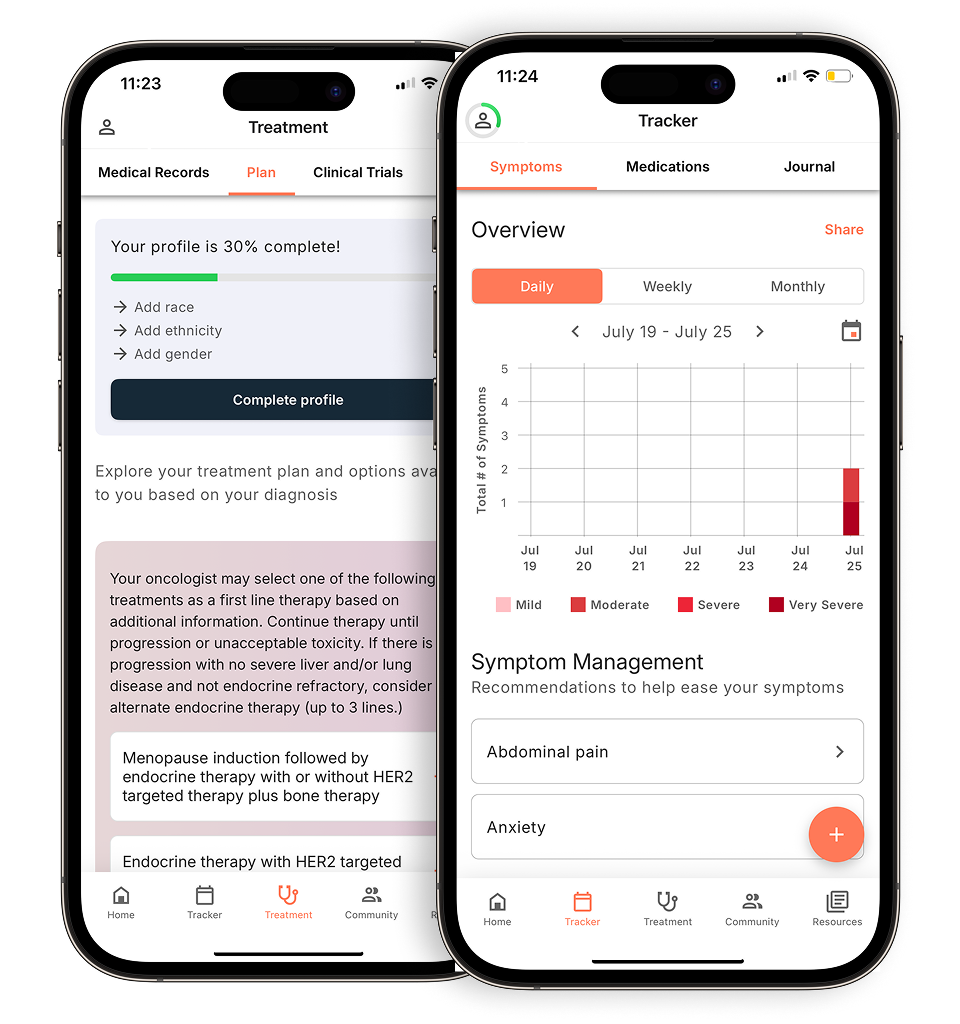

Evidence-based guidance powered by NCCN Guidelines®

Personalized treatment plans shaped by the latest oncology standards—tailored to your diagnosis.

Get started

View your personalized treatment plan in the Outcomes4Me app

Use your diagnosis to unlock personalized NCCN Guidelines®-aligned recommendations.

Continue in app

Two studies have really helped clarify this. One was a large randomized study done by the Canadian Cooperative Group. Patients were randomized to two different approaches. One was what I’ve been telling patients for the last decade. “You need to get out and exercise. I want you exercising 30 minutes, three times a week. It’s really important.” Some people will do it, some people won’t. That was one arm of the study.

The other arm randomized patients to have a trainer who held them accountable. Not just talking to the doctor every six months, but someone asking, “What have you done this week? Did you get on the treadmill?” If walking wasn’t working, they worked through other options to increase aerobic activity.

The amazing thing was that exercise worked. It worked in a really compelling way. The magnitude of benefit was just as much as the adjuvant therapy we were giving.

Think about that. Everything we put patients through, from the treatments we give to the toxicities they endure, and structured exercise with accountability, had the exact same magnitude of benefit.

Now, when I talk to patients, I don’t just say, “Go exercise.” Instead, I say if you can get access to someone who will hold you accountable, that’s where we see real benefit.

That magnitude of benefit is substantial. Exercise can’t be overestimated. It’s aerobic exercise. You don’t get credit for arm curls or weight training. Those have other benefits, but they’re not what appeared to drive this effect.

The second thing we found is that aspirin really does appear to work. Randomized studies have now come out. It may be more effective in certain subsets, such as patients with PI3 kinase alterations, but some argue that aspirin is low risk, has real benefit, and may be reasonable for many patients in this setting.

Those are the key interventions. We still recommend a low–saturated fat diet. No one has done a randomized study comparing dietary patterns, but we think it’s worthwhile. We don’t know definitively about vitamin D, but we recommend it. What we now know definitively is that aspirin and exercise make a difference.

2) Can you share your insights on the rising rates of CRC in younger adults?

What we’re seeing is what we call a birth cohort effect. Patients born starting in about the 1960s, and especially those born in the 1980s and 1990s, have a substantially higher risk of developing CRC than similarly aged patients in years past.

What does this mean? It means we’re not only seeing CRC earlier, but we’re also concerned about a potential coming wave of CRC later in life, as whatever is driving early-onset disease begins to show up as patients age.

While we talk about early-onset CRC, this may actually represent a broader shift , almost a tidal wave in epidemiology. What’s causing it? That’s the big question.

Obesity and overweight are often discussed, but that doesn’t describe most patients we see in the clinic. Some epidemiology suggests a role, but the vast majority of patients are normal weight or only slightly overweight.

There’s also discussion about changes in the microbiome and how those changes may be driven by diet. There’s data suggesting an association with high fructose corn syrup and sugary drinks, which is one of the strongest epidemiologic signals we see. Again, these are associations, not proven causes.

It’s not that we’re eating more red meat or barbecue than in the past. What has changed is the diet overall, and how that diet interacts with the microbiome.

The 1970s and 1980s were also a time when antibiotics were used a lot in children. The question is whether that widespread antibiotic exposure altered the microbiome in a way that increased cancer risk later in life.

There’s a lot of work ongoing to understand this. We’re seeing hints in mutational signatures, patterns of DNA damage that can sometimes be traced back to certain bacteria. In some patients, we can actually detect those patterns through tumor sequencing.

We don’t know the full story yet. We have some hints, but we need more data.

View part one of our recap where Dr. Kopetz explains how CRC is diagnosed, screened, and staged.

Personalized support for real care decisions

Understand your diagnosis, explore clinical trials, and track symptoms--all in one place.

Get started

Compare treatments, prepare for appointments, and track side effects—all in the app

Built for your diagnosis, Outcomes4Me gives you the tools to make confident, informed decisions—right when you need them.

Continue in app