Dr. Sara Hurvitz, a medical oncologist and clinical research leader at Fred Hutch, recently joined Outcomes4Me for an informative webinar relevant for all patients navigating their breast cancer care.

Read on for a recap of the important advancements in breast cancer testing that all patients should know.

The following questions and responses have been lightly edited for grammatical purposes.

Q: How are genomic and genetic tests different from each other?

A: I think it’s best to sort of distinguish these tests into two buckets. The first bucket is what we call germline genetic testing. And when we talk about germline, we’re talking about what genes were passed from your mom or dad down to you. And if you receive a gene from Mom and Dad, for example, relating to the BRCA gene, like a BRCA1 or BRCA2 genetic mutation, that is a mutation that is in every cell of your body and including the breast cancer cell.

If you happen to be diagnosed with breast cancer, we test for common inheritable mutations such as BRCA1, BRCA2, 2PALB, CHECK2, and the way that we test for a germline genetic mutation is either a blood test or a swab of the inside of the cheek to get some cells from there. There are easy kits that can be sent to a person’s home, and then they can do the swab and send it back in. And then those genes are tested from the cells on the lining of your inner cheek. So that is what we sort of classify as genetic testing. But saying germline makes it really clear that we’re talking about what genes you got from your mother or father relating to a risk of breast cancer or other cancers.

Genomic testing generally refers to what we call somatic testing, and that is testing the tumor itself, the tumor’s genes. Because sometimes when a cancer develops that cancer cell that was the first cell to be cancerous has genetic mutations that only affect that cancer cell and those genetic mutations continue on in that cancer cell. And you can test for those by sending a sample of the tumor and more recent tests. There are some recent tests that have been developed where you can do a blood test and look for tumor DNA to test the tumor DNA for genetic mutations. These genetic mutations, or what we call alterations, because sometimes they’re not technically a mutation, are important for us to test for in certain situations, because we have seen the development of therapies that target those mutations so medicines that can go after what’s broken in the cell as classified by that mutation. So both of these classes, germline and somatic, are genetic alterations.

Evidence-based guidance powered by NCCN Guidelines®

Personalized treatment plans shaped by the latest oncology standards—tailored to your diagnosis.

Get started

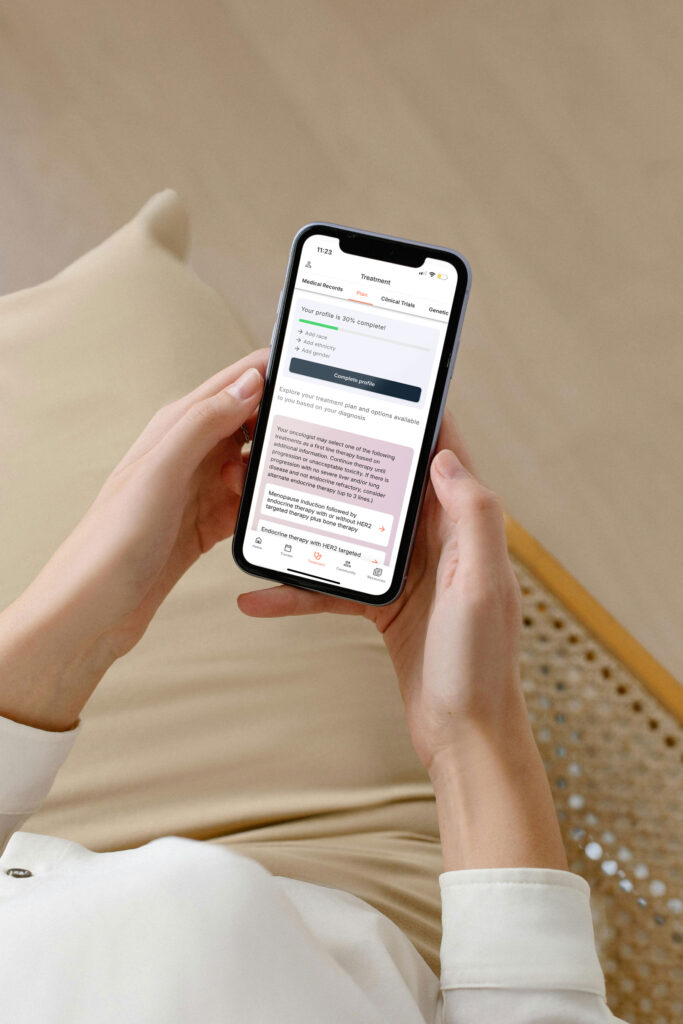

View your personalized treatment plan in the Outcomes4Me app

Use your diagnosis to unlock personalized NCCN Guidelines®-aligned recommendations.

Continue in app

Q: Should all breast cancer patients undergo BRCA1 and BRCA2 testing or is it only for those with a family history?

A: So part of my answer is my opinion, and part of it is based on our guidelines and the best available evidence. We follow what’s called the National Comprehensive Cancer Network, or NCCN Guidelines®, which is comprised of experts in the field from medical centers that are classified as NCI-designated comprehensive cancer centers. So these are the best and the brightest in the field of a particular cancer. And there are guidelines for breast cancer in particular. And if you look at the guidelines for anybody diagnosed with metastatic, Stage IV breast cancer, they should have germline genetic testing done to look for BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations. And generally it’s now done, not just for those two mutations, but a whole panel looking for other mutations that you could have inherited from Mom or Dad that may be affecting your risk for breast cancer, and now may affect what treatment is offered for early-stage breast cancer. We use factors such as family history. Do you have a family history of breast cancer? IIs there a history of ovarian cancer? Is there a history of melanoma, prostate cancer, pancreatic cancer, etc.?

Cancer care guidance for every step of your journey

Get treatment options, clinical trials, and support tailored to your diagnosis--all in one place.

Get started

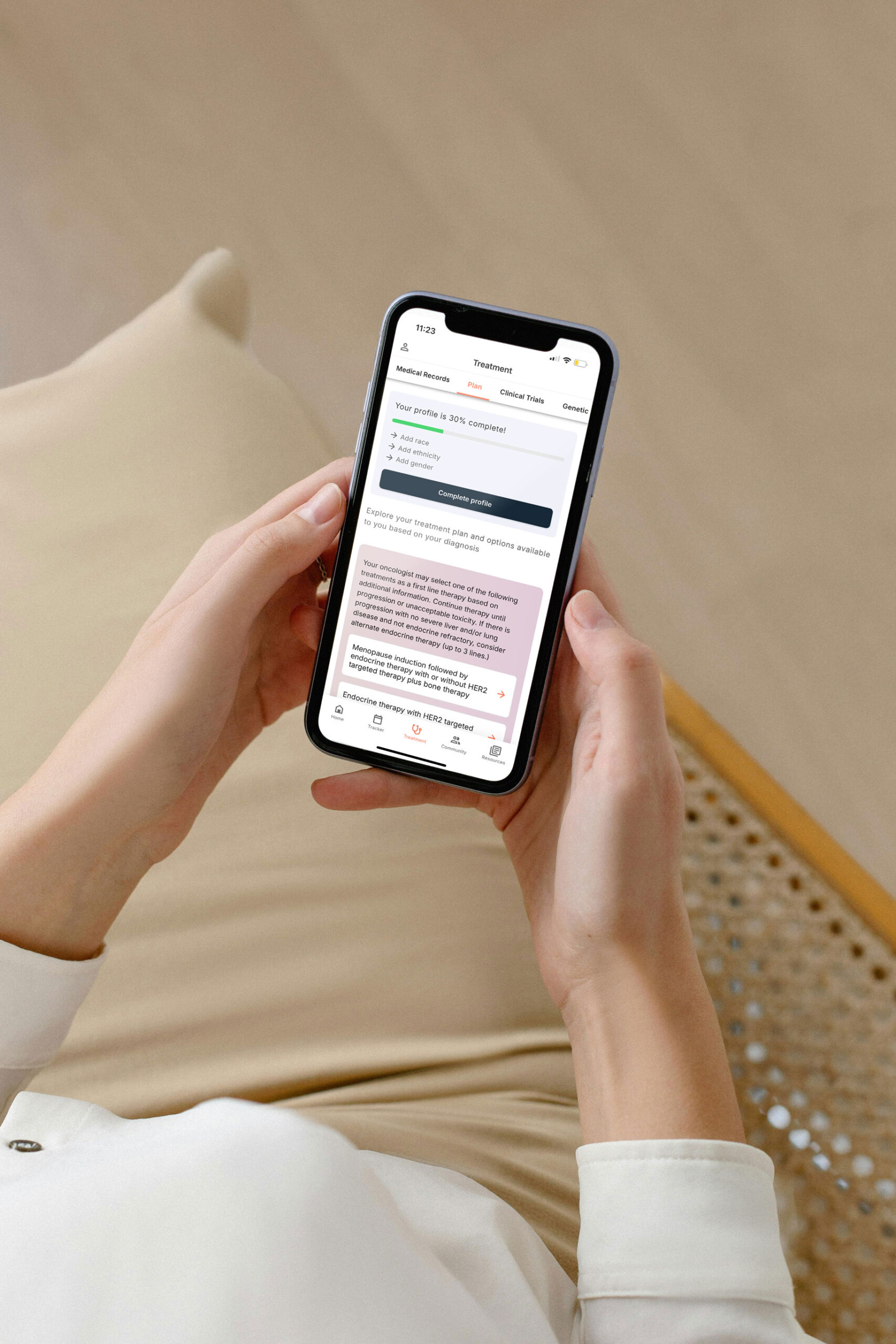

See treatment options, manage symptoms, and stay informed—all in the app

View treatment options and trials personalized to your diagnosis—plus track progress in real time.

Continue in app

And then we look at the tumor type. So for triple-negative breast cancer, I am testing pretty much everyone. And with the availability of a new drug for early-stage disease called olaparib or Lynparza, this is a drug that is very useful for patients with high-risk breast cancer that’s BRCA-associated, BRCA-mutated. And so for that reason, because we have the availability of that drug for high risk-disease, I’m recommending genetic testing for everyone, regardless of family history…and then, for the most part, it gets approved. Now, one could argue that if you have a patient with a very low-grade, early-stage breast cancer with zero family history, and it’s very early-stage and they would not be a candidate to receive olaparib, because they don’t have high-risk disease, don’t test them genetically. But I feel like the cost of genetic testing has come down substantially now that there are multiple companies able to do it. And the information can be really impactful in terms of deciding how to surgically manage the cancer and reduce the risk of another breast cancer that may not be as low risk. It may give information about management of the ovaries if they’re found to have a BRCA mutation, and it gives the family information. So, in my opinion, I think everyone should be tested, end of sentence, but it is a little bit more nuanced.

Q: What is the Oncotype DX test, and how does it help determine whether a patient needs chemotherapy?

A: Oncotype is, to make it very simple, a kind of expensive pathology second opinion. So you get your tumor tissue taken out–and this is for patients with essentially Stage I and II breast cancer, that is hormone receptor-positive, and HER2-negative. If you have a HER2-positive breast cancer, you don’t need Oncotype. If you have triple-negative breast cancer, you don’t need Oncotype. But if you have Stage I or II, including lymph nodes–one to three positive lymph nodes–Oncotype may be an option. The Oncotype test takes a sample of the tumor, which is sent in from either the core biopsy or from the surgical specimen. It’s sent to a central laboratory, and they test which genes are being expressed in that tumor cell. And they’re focusing primarily on genes that relate to hormone receptor expression–estrogen and progesterone, HER2–and what we call Ki-67, or proliferation genes. These are genes that are turned on when the cancer cell is dividing. So the more the cancer cells are dividing quickly, the higher those genes are expressed and they count up. They have this scoring system for the genes that are expressed, and they count it up, and they generate a risk of recurrence. A recurrence score. It’s called the Recurrence Score or RS. And that score can be 0, I think, all the way to 100. If the score, generally speaking, is less than 26, especially for postmenopausal women, chemotherapy is totally unnecessary because the cancer is not going to be responsive to chemo. The patient may still have a larger tumor, or have one or two lymph nodes involved. That doesn’t mean the patient shouldn’t receive anti-estrogen therapy or other therapy to treat the disease, but it tells you that chemo is not likely to impact that patient’s outcome. And that’s because chemo works when cancer cells are dividing quickly. That’s when the cancer cell is vulnerable to chemo. So if you have a cancer that took a long time to grow and the very few of the cells were dividing at a given time point, it’s going to be resistant to chemo. So in that regard, it gives us a standardized way to kind of look at how effective chemo is going to be.

If a patient has more than three positive lymph nodes, it’s not been validated to be beneficial in selecting to do chemo or no chemo. This is not a test to do to see if you can omit taking tamoxifen or an aromatase inhibitor. It’s not a test that can tell you, “Should I be using one of these new fancy drugs, the CDK 4/6 inhibitors ribociclib or abemaciclib?”

Q: For patients with hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer, where we most often hear about late recurrence, how is an OncotypeDX test helpful? Why would chemo even be a consideration if chemo only helps in the first five years after a cancer diagnosis?

A: The chemo benefits extend out many, many years beyond five years. It’s just that, inherently, the tumor is either going to be responsive to chemo or not. And that’s what you’re distinguishing. Taking five years of anti-estrogen therapy, for example,has benefits out to year 20 in patients who took it. And that’s just as far as we’ve gotten looking at that. But if you look at long-term data of using chemo or not using chemo for patients with ER-positive disease for those patients in whom their disease is sensitive to it, that effect–because you’re lowering the risk in those first five years–you’re improving long-term outcomes for those patients.

Read part 2 of our webinar recap here!

Personalized support for real care decisions

Understand your diagnosis, explore clinical trials, and track symptoms--all in one place.

Get started

Compare treatments, prepare for appointments, and track side effects—all in the app

Built for your diagnosis, Outcomes4Me gives you the tools to make confident, informed decisions—right when you need them.

Continue in app