We had the opportunity to host Assistant Professor of Urology at UCLA Health Dr. Wayne Brisbane for an illuminating discussion on the power of personalized treatment options in prostate cancer care.

Uncover how cutting-edge technology and innovative approaches are revolutionizing treatment in the full webinar, linked below.

Continue reading for some key points transcribed from the discussion.

The following questions and responses have been lightly edited for grammatical purposes.

Q: How has personalized medicine changed the landscape of prostate cancer in recent years?

A: It’s made some very important treatments. Oftentimes when we diagnose men with prostate cancer, we put them in several big buckets. These are oftentimes called their NCCN risk classifications. They were based on some initial classifications from a radiation oncologist called Dr. D’Amico who said, “Well, I need to stratify men to see who should get hormone therapy when getting radiation.”

So there’s the low-risk bucket which has traditionally been the 3 plus 3s, kind of the lower PSAs less than 10, and cancer that you can’t feel on a digital rectal exam. Then there’s this very high-risk group which has been the 4 plus 4s, PSA is greater than 20 and cancer that you can absolutely feel. There are a couple of nuances in there, but there’s this big catch-all bucket in the middle. That’s the 3 plus 4s and 4 plus 3s and PSA is between the 10 and 20 groups.

I think we’ve done a good job of further stratifying men out over the last decade using genomic markers and imaging. Some AI can take these various input streams and further risk stratify men. The effort is mostly to de-intensify cancer treatment when it’s okay to preserve quality of life, but also to intensify treatment when that’s required to achieve better longevity.

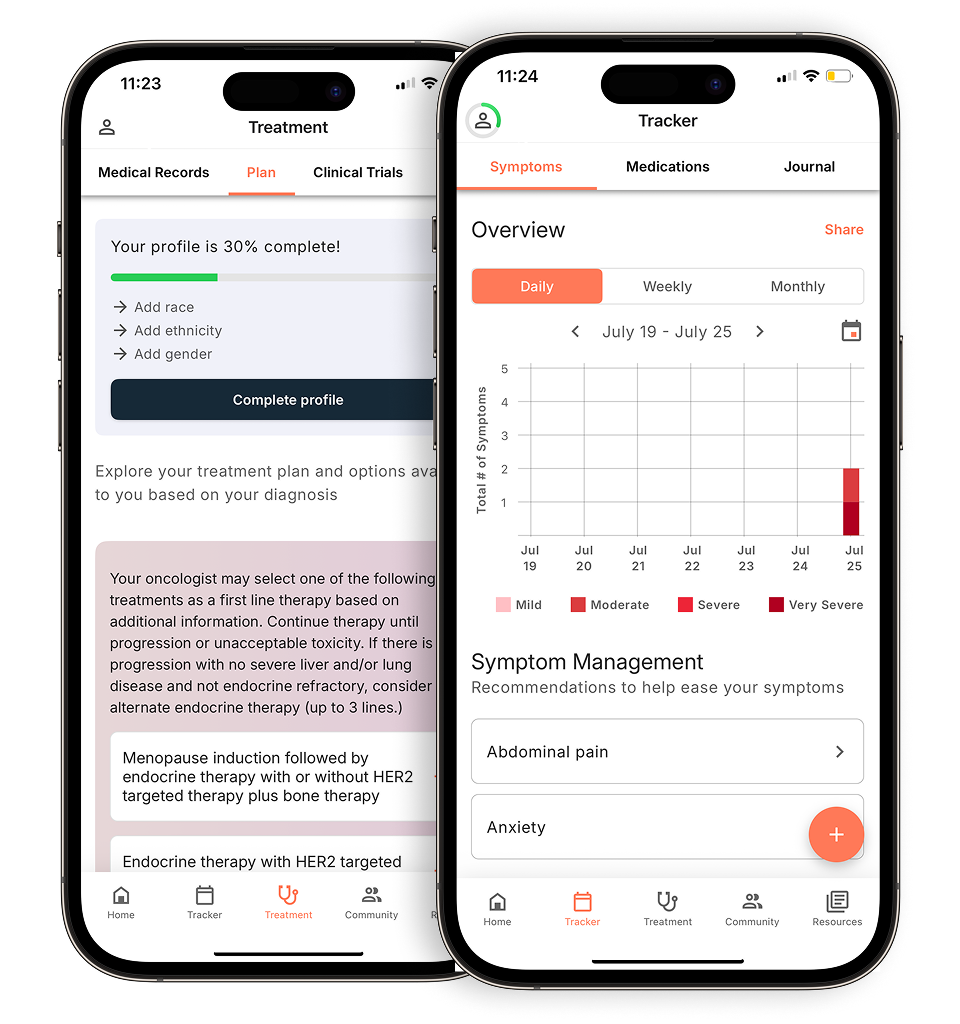

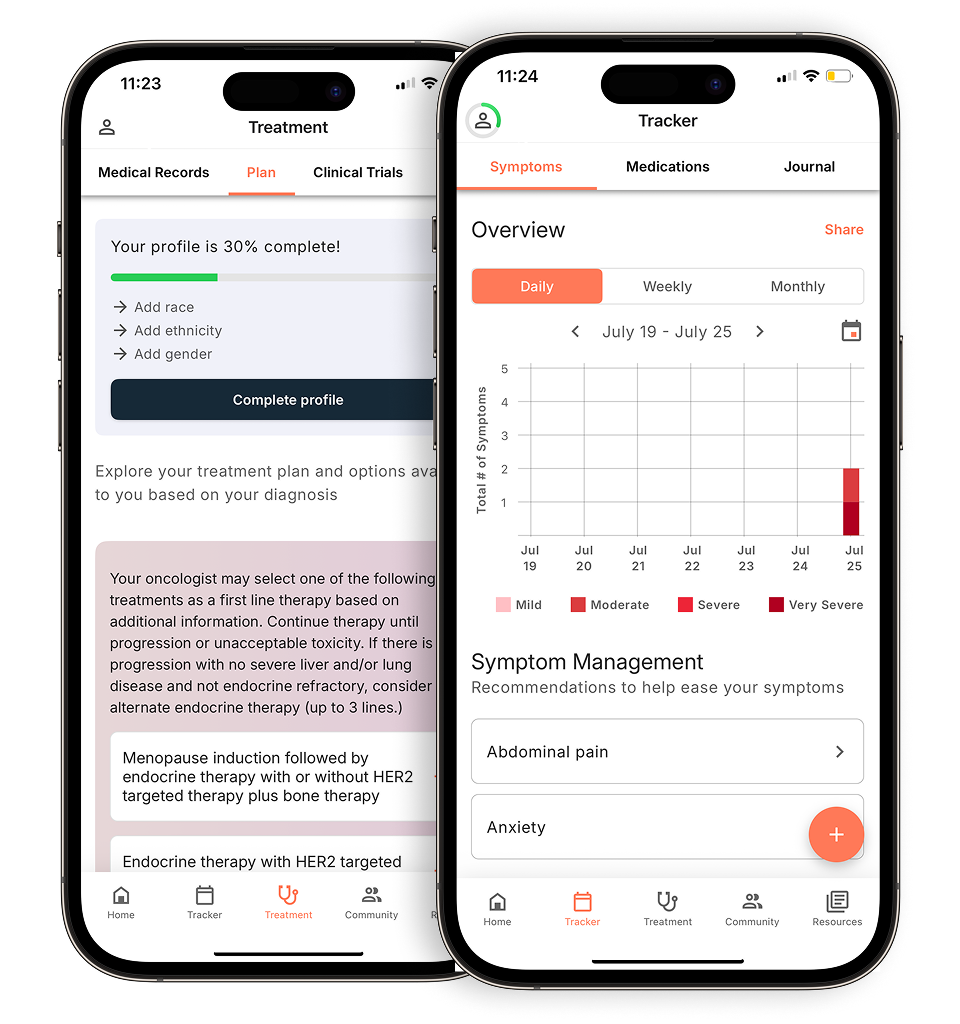

Evidence-based guidance powered by NCCN Guidelines®

Personalized treatment plans shaped by the latest oncology standards—tailored to your diagnosis.

Get started

View your personalized treatment plan in the Outcomes4Me app

Use your diagnosis to unlock personalized NCCN Guidelines®-aligned recommendations.

Continue in app

Over the last decade, we’ve been using various information pieces like genomics and imaging and mixing and matching them with some AI to improve personalization. I think you’ll only continue to see that as we get some targeted therapies.

We have some cool classes of medications that are coming in like Pluvicto that are brand new and we usually start those at the end of treatment. These are men who have metastatic disease that’s very aggressive. They failed some of the first-line things and then moved farther and farther up in the treatment regimen. While we’re finding that that does work, the next step is to figure out who it works best for. That’s the idea of personalized medicine or precision medicine is the other name.

Q: How do you determine who’s a candidate for active surveillance versus treatment?

A: Active surveillance, for those of you who aren’t as familiar with it, is basically watching cancer with the promise that we’re going to catch it before it spreads. There have been several really important trials looking at this, but there’s a well-cited one called ProtecT done in the UK where they randomized men to get something called active monitoring. That’s very similar to active surveillance, but it’s not perfectly the same.

The interesting thing about this trial is they were able to flip a 3- headed coin and say, “Okay, Mr. Smith, you’re going to radiation, Mr. Jones, You’re going to surgery. Mr. Brown, you’re going to go to active monitoring or active surveillance.”

The interesting thing about this trial is it started out with all-comers. Basically, if you had prostate cancer, you could be enrolled in this trial. It did have a lot of guys with lower-risk prostate cancer, but the really powerful thing about this trial is it compared men a long way into the future. For this trial, you can’t see any separation between these active monitoring, radical prostatectomy, and radiation therapy, indicating that active surveillance for the appropriate person may be a very good treatment strategy.

Now, there’s a couple of nuances. We did find that people who were on active surveillance had a couple more metastases. That was a very small relative risk, but it was there. Initially, we thought that it would be a concern at the 10-year endpoint. We followed these men another few years and didn’t find that was translating into people dying, so it seemed like it was very safe to be on active surveillance.

It also took into account that a lot of men who started off with this active monitoring did get some kind of treatment. About half of these men at 10 years had gotten some kind of treatment. If you start with active monitoring, there’s a chance that you’re going to need to get some treatment, but this is a 10-year risk. You can go for some time without getting treatment side effects.

I think that active monitoring is something that’s very well-established at this point and is a good treatment for many men. It’s just figuring out who is a good candidate and that requires a lot of imaging and genomic tests.

We’re trying to keep people on active surveillance for a long time without doing a ton of biopsies. That’s always been a frustration for men who are on active surveillance, but some very thoughtful people are looking into this and some great clinical trials are underway in order to help refine our active surveillance protocols.

Q: Besides biopsies, what are some other ways to monitor active surveillance?

A: There’s a calculator that’s freely available from work done out of the U.K. It looks at STRATCANS and it’s for men who are on active surveillance trying to intensify or de-intensify the follow-up and biopsy schedule. Using more things like PSA, MRI, I’m using some micro-ultrasound, and then we’re trying some AI.

I think there are some clinical trials that are run out of a group at Cornell that are using PSMA, so we’re going to see a lot of these other markers for progression which hopefully have some really good powers to predict who’s going to be a good candidate and when we need to intervene. There are also other ways like using the genomic tests.

The Movember group is really trying to do this in a prospective manner, along with several others like the Canary PASS program, and active surveillance cohorts like the ones we have at UCLA, Hopkins, Sunnybrook, and UCSF. They’re all trying to figure out how do we make sure that we can get people safely on active surveillance, minimize the number of interventions so that we can follow them safely and intervene when we need to, but also make sure that they don’t feel oppressed by the number of biopsies and MRIs that they have to do.

To view the entirety of Dr. Brisbane’s Ask the Expert webinar, click here.

Related Topics

- Understanding Prostate Cancer Biomarker Testing

- Therapy vs. Surgery for Prostate Cancer

- Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Treatment Options

- How Does Hormone Therapy Work for Prostate Cancer?

- Advances in Immunotherapy for Prostate Cancer Treatment

- What to Know About Robotic Surgery Prostate Cancer

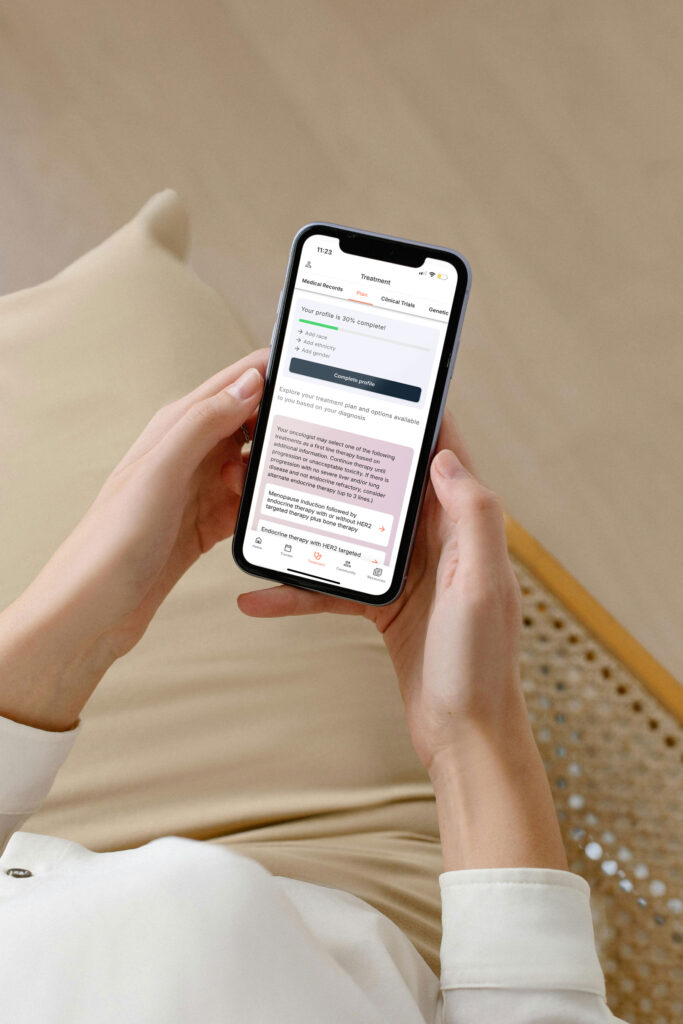

Personalized support for real care decisions

Understand your diagnosis, explore clinical trials, and track symptoms--all in one place.

Get started

Compare treatments, prepare for appointments, and track side effects—all in the app

Built for your diagnosis, Outcomes4Me gives you the tools to make confident, informed decisions—right when you need them.

Continue in app