If you or a loved one has been recently diagnosed with prostate cancer, you may feel overwhelmed with the amount of information available. In our discussion with genitourinary oncologist Dr. Atish Choudhury at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, we break down the latest advances in prostate cancer care. Watch the full webinar for insights on radiation therapy, hormone therapy, nutrition, and more.

Keep reading for a deep dive into radiation therapy transcribed from the webinar.

The following questions and responses have been lightly edited for grammatical purposes.

1) What is a Gleason score and how does it influence treatment?

To understand the Gleason score, it’s important to know what the prostate is. It’s a normal gland in the body that makes seminal fluid. When a pathologist looks under the microscope at the biopsy specimens taken, they give us information on how aggressive the cancer looks. This gives us a sense of whether it’s a low-risk, intermediate-risk, or high-risk cancer that needs to be treated appropriately.

The Gleason score is the sum of two numbers called Gleason patterns. If the pathologist looks under the microscope and the cancer they see is forming somewhat normal-looking glands similar to a normal prostate, they’ll call it a Gleason pattern 3. If it forms abnormal-looking glands, they call it Gleason pattern 4. If it’s not forming much in the way of glands at all, they call it Gleason pattern 5.

The score is the sum of the most common pattern with the second most common pattern. If all the cancer that the pathologist sees is Gleason pattern 3, we call that 3 plus 3 equals 6, which is considered a low-risk cancer that we usually just watch. However, if all they see is Gleason pattern 5, it’s 5 plus 5 equals 10. That’s a high-risk cancer that needs an aggressive kind of treatment. Everything else falls somewhere in between. For example, if there’s more Gleason pattern 3 than Gleason pattern 4, we call that 3 plus 4 equals 7. If there’s more pattern 4 than pattern 3, we call that 4 plus 3 equals 7. Having more pattern 4 means that it’s a slightly more aggressive cancer than the other way around.

The Epstein Grade Groups is a different scoring system that’s the easiest way to understand where on the spectrum a particular patient’s cancer is. It’s on a scale of 1-5. Gleason 6 cancer is one on that scale and Gleason 9 or 10 cancer is 5 on that scale. Again, everything else is more in the middle, so it makes it easier for a patient to understand how aggressive their cancer is and what we need to do to treat it.

Evidence-based guidance powered by NCCN Guidelines®

Personalized treatment plans shaped by the latest oncology standards—tailored to your diagnosis.

Get started

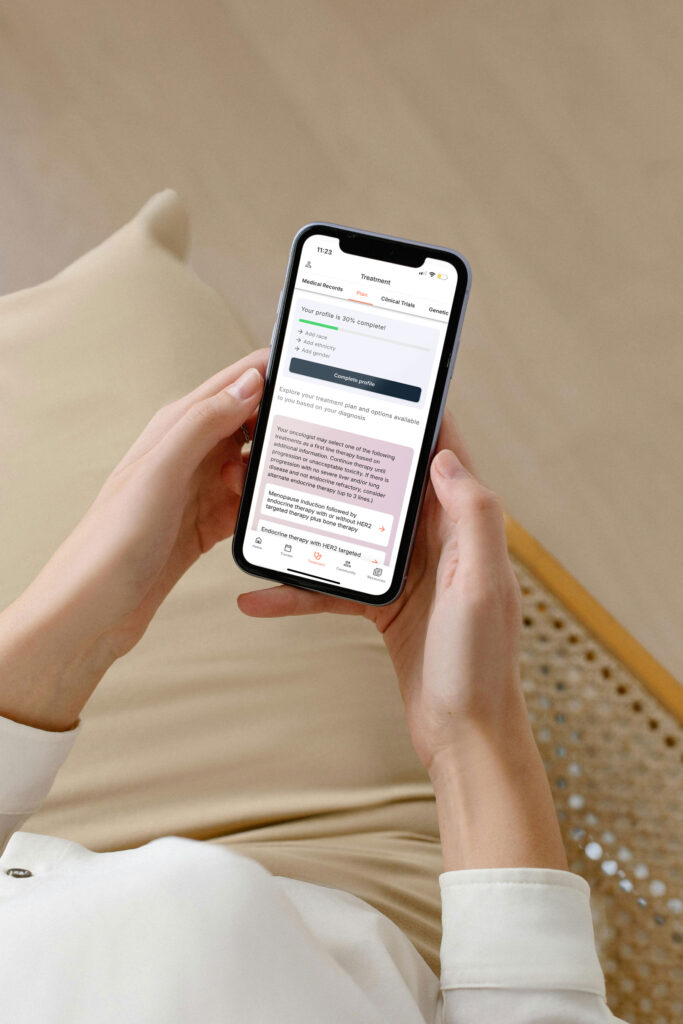

View your personalized treatment plan in the Outcomes4Me app

Use your diagnosis to unlock personalized NCCN Guidelines®-aligned recommendations.

Continue in app

2) Do radiation and prostate surgery have similar effectiveness?

In all the decades of prostate cancer research, there’s been only one randomized clinical trial where patients were randomized to have surgery versus radiation and there was a third arm on that trial which was just initial monitoring.

That trial was performed out of England and what they showed was whatever you did at the beginning, whether it was surgery, radiation, or monitoring for localized and screen-detected prostate cancer, the likelihood of dying of prostate cancer was very low at a 10 or 15-year timeframe. When they looked at the data, the likelihood of the spread of prostate cancer to other parts of the body was about double for the patients who were initially monitored compared to the people who were initially treated. There are situations where we would recommend initial treatment rather than monitoring, but when you look at the risk of metastasis of prostate cancer over a 10 or 15-year period, it was about identical for surgery compared to radiation. That’s the only randomized evidence that we have.

When we make recommendations to our patients, we have to individualize based on the features of their cancer, but also their age, performance status, and preferences because there are reasons to favor surgery for some patients and reasons to favor radiation for others.

3) Is there a specific diet plan you recommend before having radiation therapy?

The dietary recommendations we make are not based on a lot of clinical trial evidence. It’s just observations based on our patients and epidemiology as well. The diets we recommend for our cancer patients are very similar to what the American Heart Association would recommend for their heart patients or what the American Diabetes Association would recommend for patients to prevent diabetes. It’s mostly a plant-based diet based around healthy fruits and vegetables and limiting processed foods, processed carbohydrates, and animal-based proteins and fats.

Cancer care guidance for every step of your journey

Get treatment options, clinical trials, and support tailored to your diagnosis--all in one place.

Get started

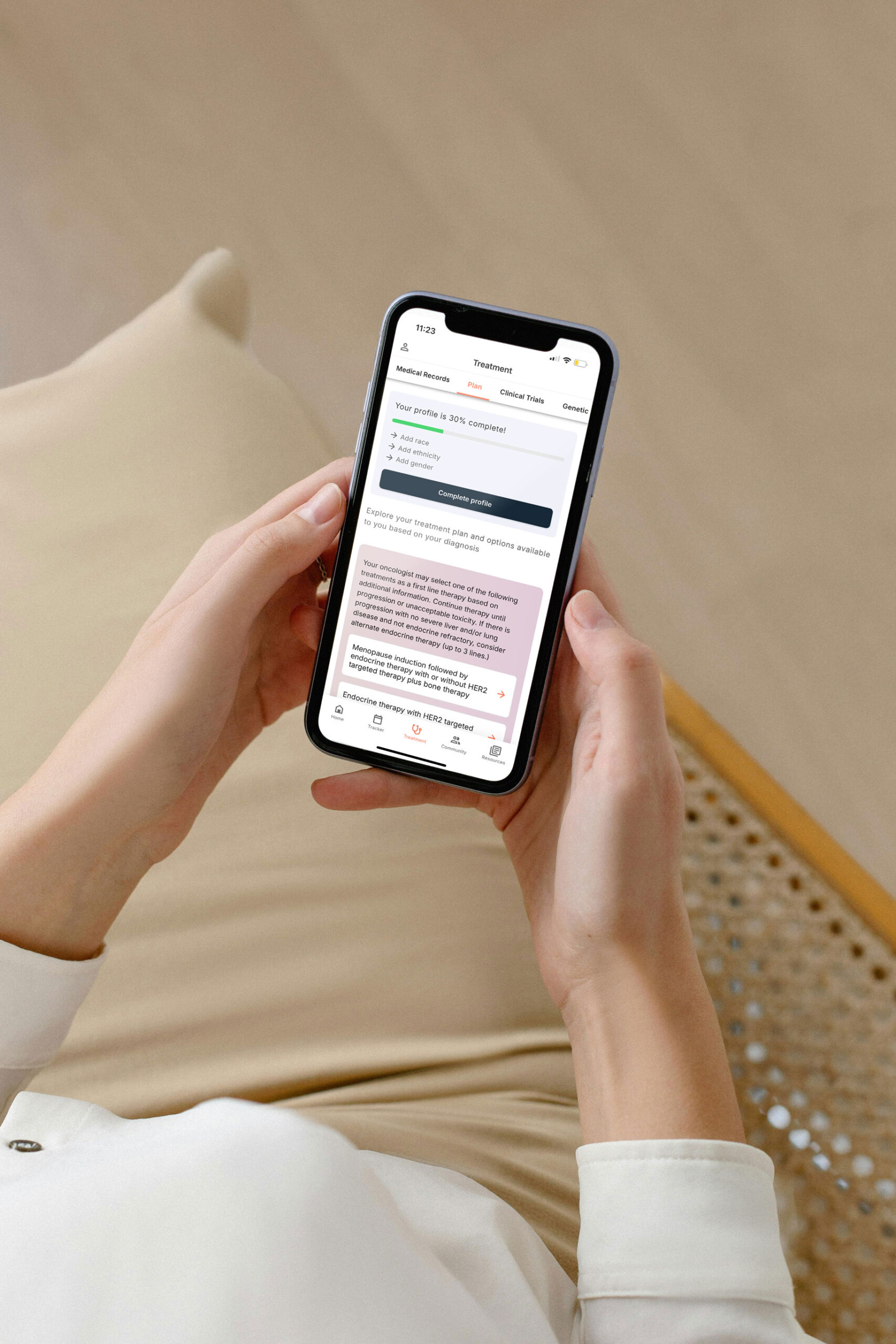

See treatment options, manage symptoms, and stay informed—all in the app

View treatment options and trials personalized to your diagnosis—plus track progress in real time.

Continue in app

Our Western diet might be a giant bowl of pasta or huge cuts of steak and that’s your meal. What we would recommend is diverse kinds of fruits and vegetables, salads, cooked vegetables, and smaller portions of carbohydrates. The carbohydrates should be less processed and also smaller portions of meat-based proteins. The things to avoid in general are very processed foods and foods with a very high glycemic index like too much rice, potatoes, and potato chips. Those all come out epidemiologically as being very poor in terms of weight and metabolic parameters. Most fat and protein should be from plant-based sources like nuts and avocados, but even dairy sources are fine. Full-fat yogurts are okay as part of this healthy Mediterranean-type diet.

The thing we try to have our patients avoid is fad diets. Diets where you’re focusing on a specific food rather than the diversity of foods that Mother Nature has provided us. We need our patients to find good, tasty, and helpful food so they can help prevent weight gain and poor metabolic outcomes that might increase the risk of heart disease, diabetes, and things like that down the line.

When you’re thinking about radiation, the main concern in terms of diet is the effects on the GI tract. Some people can get an upset stomach, gas, diarrhea, and things along those lines. Try to keep things a little bit on the blander side, less acidic, less spicy, less heavy oils, and fewer things that’ll upset the GI tract. Oftentimes having plenty of fiber will help bulk up stool. Sometimes excess fiber can cause irritation, so there needs to be individualization of your own symptoms and what your radiation oncologists might recommend.

4) What’s the difference between proton beam therapy, high-dose radiation, and seed placement therapy?

There are two primary ways to deliver radiation. One is implanted radiation within the prostate and the other is external radiation. The implanted radiation comes in different forms.

There’s something called low-dose brachytherapy where they implant little radioactive pellets throughout the prostate that remain in the body and radiate the prostate for several months after the implantation. It’s a one-time procedure. Then, there’s something called high-dose brachytherapy where you might go to the hospital and have a procedure where they insert a catheter within the prostate and give off radiation over a 15-minute period and give high doses of radiation directly to the prostate that way.

There are many different ways to get external radiation. External radiation is a process where you might go into a radiation facility daily over some number of days. You’re not radioactive because there’s nothing radioactive that’s being implanted into you.

The most common form of radiation is photon beam radiation. Most classically, external radiation for prostate cancer is given daily over a 44-day period. If you go Monday through Friday, it’s about 9 weeks which is a very long course. More recently, we found that if you can reduce the number of days that patients get radiation to maybe 20 or 28 fractions rather than 44 and just give higher radiation doses per treatment, the outcomes of both cancer control and side-effect profiles are about similar. Having a slightly shorter course of treatment is more convenient for many patients.

There is another form called proton beam radiation. Protons are heavier particles, so the marketing advantage of protons compared to photons is because they’re heavier particles, you can design a radiation plan where the particles stop more abruptly. You can treat the entirety of the prostate with less radiation exposure to the surrounding organs like the bladder and the bowel which can lead to some of the late-term complications of radiation. While there’s marketing around these potential benefits, that hasn’t been demonstrated in clinical trials. Because it’s about double the price of your standard photon beam radiation, most insurances won’t cover it.

There are also theoretical reasons why protons might be equivalent. By being heavier, there’s a bit more exposure to the skin so it can lead to more skin irritation than photon beam radiation. The way that photon beam radiation is delivered in the modern era uses very sophisticated techniques where they map exactly where the prostate, bladder, and bowel are. Even with photons, you can have a sophisticated plan where the prostate gets high doses of radiation, but the bladder and the bowel get lower doses.

In the modern era, there still can be side effects related to the bladder and the bowel, but certainly less than what it used to be when the radiation was given without all this sophisticated mapping. I’m not a radiation oncologist, so that was a medical oncology perspective on that. You should definitely consult with an expert radiation oncologist to get more details about the different approaches.

Watch the entirety of Dr. Choudhury’s webinar here.

Related Topics

- Understanding Prostate Cancer Biomarker Testing

- Advances in Immunotherapy for Prostate Cancer Treatment

- Metastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer Treatment Options

- How Does Hormone Therapy Work for Prostate Cancer?

- How Precision Medicine Can Help With Prostate Cancer

- What to Know About Robotic Surgery Prostate Cancer

Personalized support for real care decisions

Understand your diagnosis, explore clinical trials, and track symptoms--all in one place.

Get started

Compare treatments, prepare for appointments, and track side effects—all in the app

Built for your diagnosis, Outcomes4Me gives you the tools to make confident, informed decisions—right when you need them.

Continue in app