The role of biomarker testing in personalized lung cancer treatment

Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) is a complex diagnosis with many different subsets that can be difficult to navigate. In our webinar with Mass General Cancer Center’s Dr. Jessica Lin, we break down some of the mutations that occur in NSCLC and how biomarker testing can help guide personalized treatment plans.

You can watch the full informative discussion below.

For an overview of mutations in NSCLC, keep reading for the key discussion points transcribed from the webinar. You can also refer to our Q&A with Dr. Lin for further insights on biomarker testing and how it works, here.

The following questions and responses have been lightly edited for grammatical purposes.

1) Do you often see multiple driver mutations or is it typically a single driver mutation that exists?

Almost always there is a single oncogene driver for lung cancer. If a patient has biomarker testing done and the NGS report shows an EGFR mutation, there probably isn’t going to be an ALK rearrangement or a KRAS mutation as well. If a patient’s NGS report comes back showing a HER2 mutation, there probably isn’t going to be a classical EGFR mutation also. There have been very rare case reports where more than one oncogene driver has been identified in a patient’s lung cancer at initial diagnosis.

Evidence-based guidance powered by NCCN Guidelines®

Personalized treatment plans shaped by the latest oncology standards—tailored to your diagnosis.

Get started

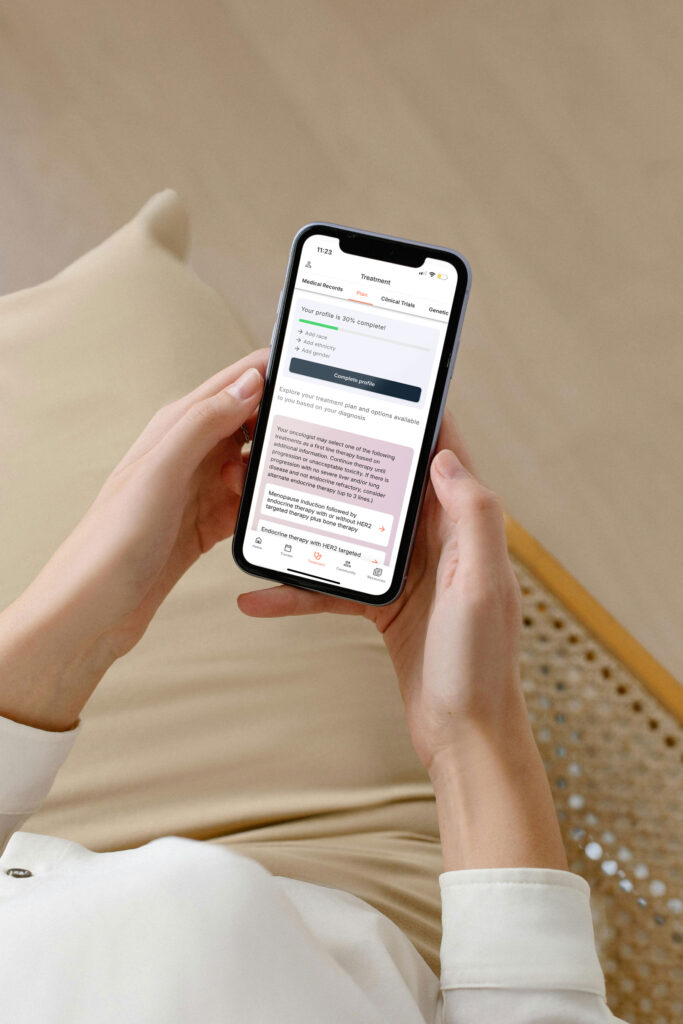

View your personalized treatment plan in the Outcomes4Me app

Use your diagnosis to unlock personalized NCCN Guidelines®-aligned recommendations.

Continue in app

The timing of the biomarker testing matters. For patients who have an actionable target (like an EGFR mutation or an ALK rearrangement identified in their lung cancer) and start with targeted therapy, some oncologists repeat the biopsy and redo the gene testing if their cancer relapses and starts growing again. At that time point, we often find mutations in more than one oncogene driver. However, that is a very distinct scenario from the initial lung cancer diagnosis for the purposes of treatment decision-making.

2) What are some of the more common mutations you see in your clinic?

The classical EGFR mutations are found anywhere from 10-15% of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Another common one is ALK rearrangement. ALK gene rearrangement is seen anywhere from 3-5% of patients with lung cancer. If this is the case, doctors may discuss ALK inhibitors like lorlatinib or alectinib.For patients that have surgically resected ALK-rearranged lung cancer, we use ALK-targeted therapy post-operatively.

There are other gene rearrangements like ROS1 gene rearrangement or RET gene rearrangement. These are both seen anywhere from 1-2% of patients with lung cancer. There are other mutations in genes. The MET exon 14 skipping affects the MET gene and it’s seen in 2-4% of patients who have lung cancer and we have HER2 gene mutations that are seen in 2 -3% of patients.

I have to mention mutations in KRAS because we’ve known about KRAS mutations for a very long time. We used to refer to KRAS mutations as being undruggable because there were so many challenges with developing targeted treatments. It was such a difficult feat, but over recent years, there have been targeted therapies that have been successfully developed for a specific subtype of KRAS mutation called G12C. There are other subtypes of KRAS mutations where targeted therapies are now being rapidly developed as well. KRAS mutations are very common in lung cancer. The G12C KRAS mutations are seen in about 13% of patients with lung cancer, so that is another important one to watch out for.

3) Could you expand more on EGFR mutations and what treatment options are available?

There are so many layers to the discussion about EGFR mutation. First, not all EGFR mutations are the same. There are many subtypes of EGFR mutations with different treatment paradigms in lung cancer. Often when we use the term EGFR-mutated lung cancer, we are referring to lung cancers with classical EGFR mutations. These are the most common EGFR mutations that we see in lung cancer.

Specifically, there are two classical EGFR mutations. One is EGFR exon 19 deletion and the second is EGFR L858R mutation. These are the ones where the EGFR inhibitor osimertinib and others have been used for years showing really great effectiveness, but there are other EGFR mutations where pills like osimertinib don’t work as well. That’s where we pull in different EGFR-targeted therapies or different treatment strategies.

That’s an important point to make. If you’re told that your lung cancer has an EGFR mutation, it’s important to learn what kind of EGFR mutation it is because that affects what the optimal treatment is for the next step.

The second point about EGFR mutations is there are a number of different EGFR-targeted strategies being used in the clinic. We often talk about drugs like osimertinib when you’re initially diagnosed, but there are later treatment options that are directed toward the EGFR mutation that your oncologist can turn to if the cancer were to grow. Having a biomarker identified in lung cancer is not only important for the first treatment decision, but it also affects subsequent treatment options and optimal clinical trials to consider down the line as well.

The final third point I will make is that EGFR-mutated lung cancer is the first subtype of lung cancer where targeted therapy has moved from being used only in patients with advanced-stage lung cancer to being used for earlier stages as well. Let’s say a patient has Stage I or Stage II, EGFR-mutated lung cancer that was resected surgically and then received post-operative chemotherapy. A couple of years ago, that may have been the end of it. Now we recommend following with post-operative EGFR-targeted therapy because we have clinical trial data showing that doing so can improve the patient’s disease-free survival and overall survival. This is one subtype of lung cancer where targeted therapy is used in earlier-stage lung cancer.

Watch the full webinar with Dr. Lin here.

Personalized support for real care decisions

Understand your diagnosis, explore clinical trials, and track symptoms--all in one place.

Get started

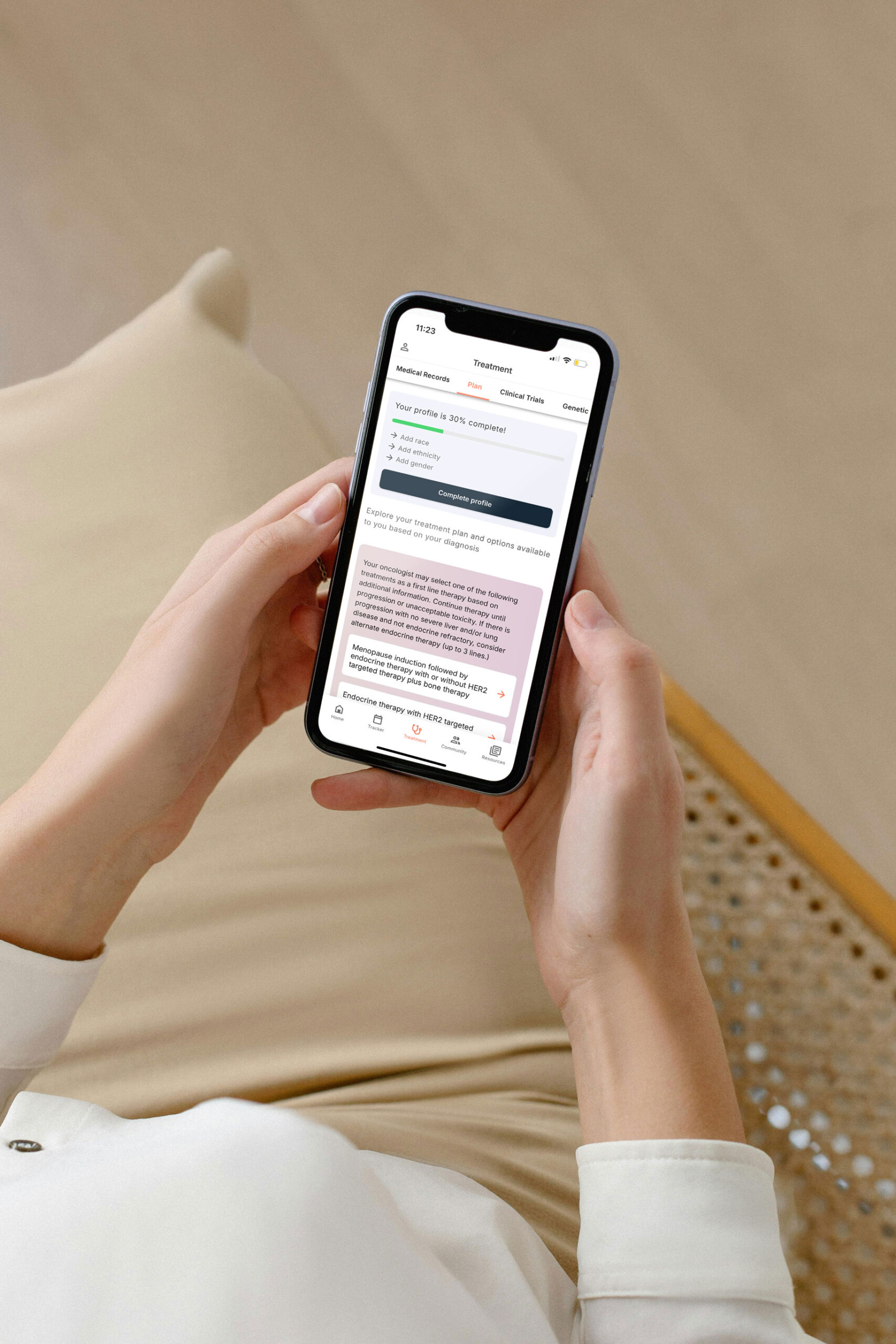

Compare treatments, prepare for appointments, and track side effects—all in the app

Built for your diagnosis, Outcomes4Me gives you the tools to make confident, informed decisions—right when you need them.

Continue in app