We recently had the privilege of speaking with Stanford University School of Medicine’s Dr. Bita Fakhri for an in-depth conversation exploring how CLL is diagnosed, what your stage means, and how molecular markers guide care.

The following questions and responses have been lightly edited for grammatical purposes.

1) What is CLL, and how does it differ from other types of leukemia and lymphomas?

Dr. Fakhri: CLL starts in the bone marrow, which I always describe as a factory that produces three major cell lines: white cells, red cells, and platelets.

White cells are a broad umbrella with different subsets underneath it.

Red cells carry hemoglobin, which binds oxygen and delivers it throughout the body. When hemoglobin drops, people feel fatigued, have less energy, and may develop chest pain or shortness of breath with exertion because their tissues aren’t getting enough oxygen.

Platelets are the clotting cells. They’re what stop bleeding when you have a cut or an internal bleed.

In CLL, the issue is with lymphocytes, a subset of white cells. A population of lymphocytes starts to acquire abnormal immune markers on their surface, which makes them dysfunctional. We need lymphocytes for two main reasons: to fight viral infections and to act as first responders when any kind of cancer develops.

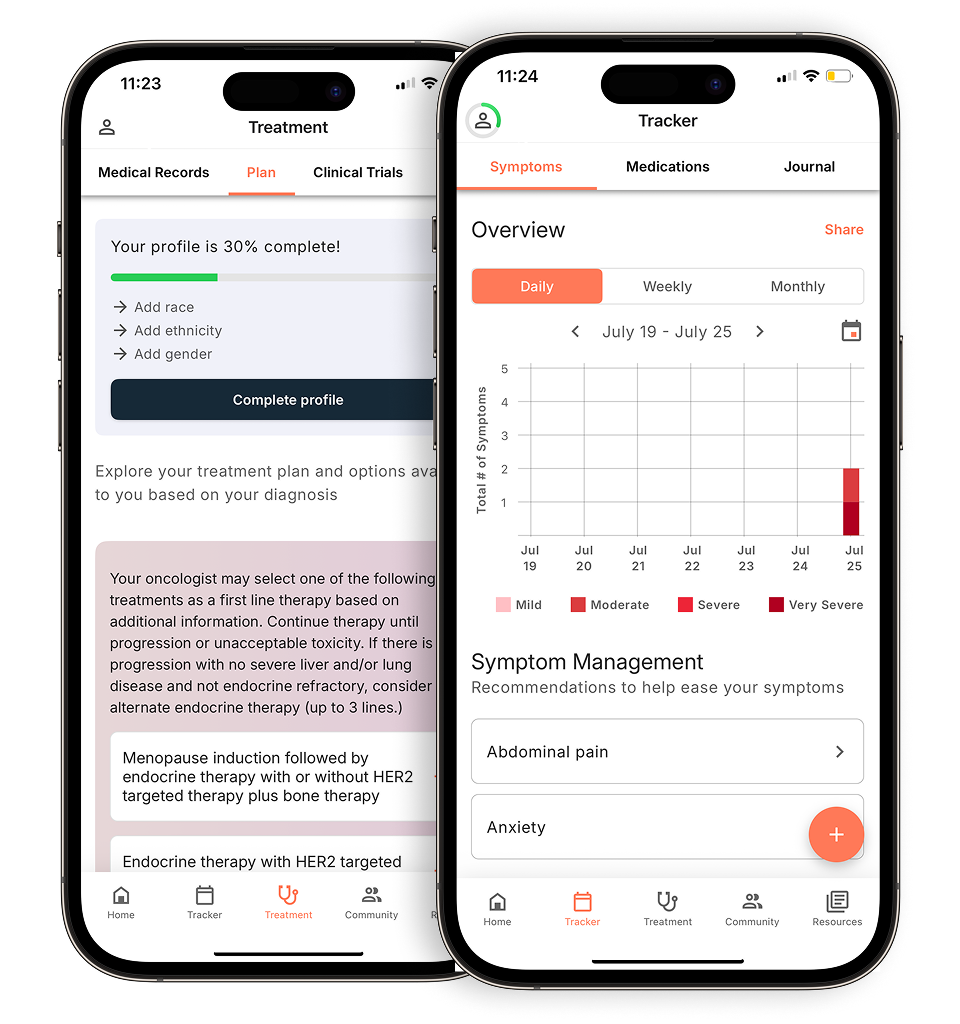

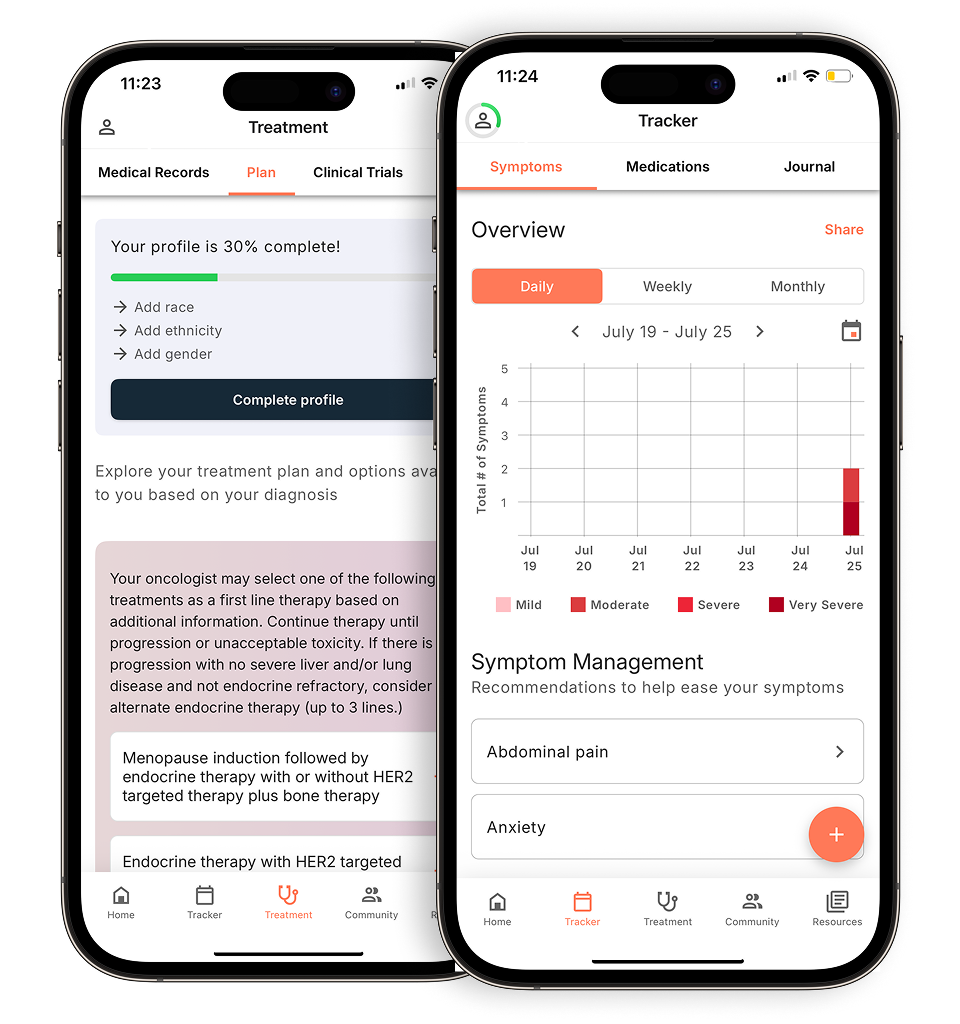

Evidence-based guidance powered by NCCN Guidelines®

Personalized treatment plans shaped by the latest oncology standards—tailored to your diagnosis.

Get started

View your personalized treatment plan in the Outcomes4Me app

Use your diagnosis to unlock personalized NCCN Guidelines®-aligned recommendations.

Continue in app

In CLL, these lymphocytes become dysfunctional because of those abnormal markers. They keep growing in the bone marrow to the point that they crowd out normal production, and that’s when we start to see the hemoglobin and platelet counts go down.

Because the bone marrow makes blood, CLL behaves differently from solid cancers. Solid cancers, like breast cancer, start in one area and then spread locally before traveling to distant organs and becoming metastatic. But blood is everywhere in the body, and lymphocytes travel through the lymph nodes, the battlefields of the immune system. When you have too many lymphocytes, those lymph nodes can enlarge, which we call lymphadenopathy. The spleen, the largest lymph node, can enlarge as well.

That’s the general picture of CLL: a leukemia of abnormal lymphocytes that continue to grow over time.

2) Can you explain how CLL is staged?

Dr. Fakhri: First, it’s really important to understand that a stage IV CLL diagnosis is not terminal. Staging in CLL is very different from staging in solid cancers.

We use two main staging systems. One is the Rai system, which includes five stages, from 0 to IV:

- Stage 0: A patient has an elevated lymphocyte count. This is something seen on a blood test when the absolute lymphocyte count goes up.

- Stage I: Lymphocytes start residing in the lymph nodes, and there are enlarged nodes on exam—in the neck, underarms, or groin.

- Stage II: The liver or spleen becomes enlarged.

- Stage III: The marrow becomes crowded out by abnormal lymphocytes and hemoglobin starts to drop.

- Stage IV: The marrow becomes crowded out by abnormal lymphocytes and platelet count starts to fall.

That’s the Rai staging system, which basically reflects how extensive the CLL involvement is in the body. Someone can be a stable stage IV CLL patient—with a hemoglobin around, say, 10.8 or 11, and platelets around 80—and still be completely asymptomatic and not need treatment. Staging does not dictate when therapy is needed; it just tells us how advanced the disease is.

There’s also a European system called the Binet staging system, stages A, B, and C, based on hemoglobin, platelets, and the number of lymph node areas involved. In the U.S., we mostly use Rai.

Staging is the older way of looking at CLL. Before we understood the molecular profile of the disease, staging was our main tool. For example, someone with stage IV disease needed closer monitoring to make sure platelets didn’t continue to drop to a level where bleeding becomes a risk.

Nowadays, we have the advantage of using specific molecular features to help us understand how a person’s CLL is likely to behave, and those markers are hugely important in guiding prognosis and treatment decisions.

One of the most important things that we use in CLL is the FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization) panel, which looks at the chromosome abnormalities inside the CLL cells. This doesn’t mean if you have a chromosome abnormality on a CLL FISH panel, you have it in your other cells, and you have basically passed it to children, or you have inherited it from your parents. The FISH panel that I’m talking about is chosen abnormalities inside the abnormal lymphocytes that define your diagnosis of CLL.

Check out part two of our recap with Dr. Fakhri to learn more about the important biomarkers that help guide treatment decisions in CLL.

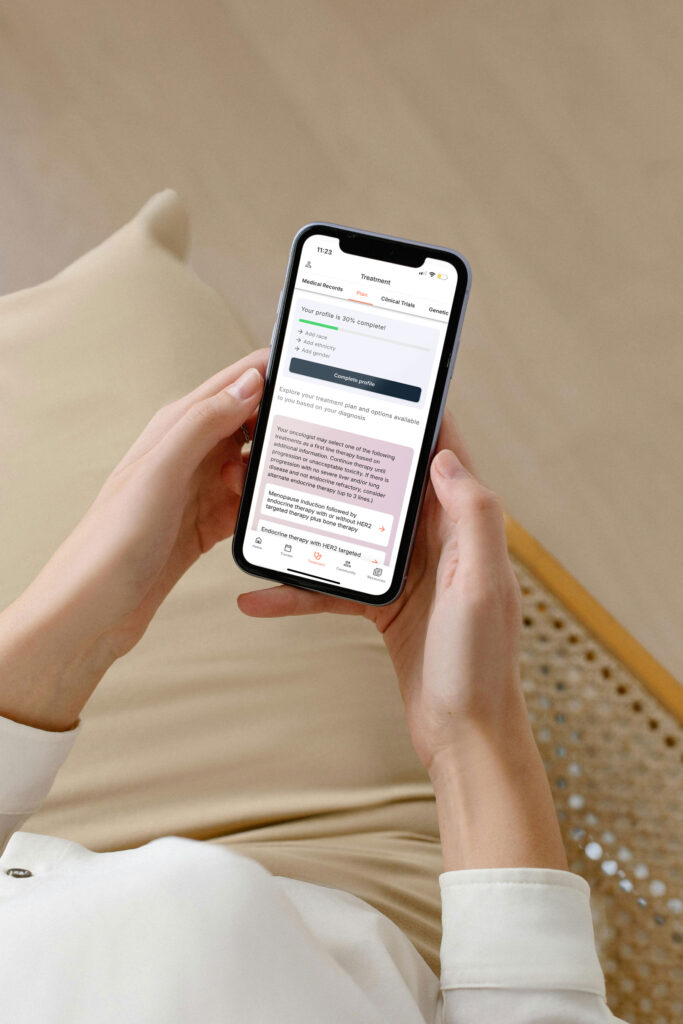

Personalized support for real care decisions

Understand your diagnosis, explore clinical trials, and track symptoms--all in one place.

Get started

Compare treatments, prepare for appointments, and track side effects—all in the app

Built for your diagnosis, Outcomes4Me gives you the tools to make confident, informed decisions—right when you need them.

Continue in app